When I was five or six, I wanted to work in physics. I was obsessed with the Space Shuttle — I even had a massive poster of the Space Shuttle bought from Birmingham’s old Science Museum by the canal (RIP to that fantastic place) on my bedroom wall. Birthday and Christmas presents often had a lunar or Astro theme.

It soon became apparent that I did not have the brain or aptitude (or Grades) for a scientific vocation, but I often wonder how different things would have been if I had. What if I pursued a scientific and mathematic path instead of working in the arts and culture sector? We all have these thoughts at times, but I have been having them a lot lately as my Birthday approaches. But then again, maybe the outcome would be the same, and I would be exactly where I am now, writing this newsletter to you.

I still love space and rockets and harbour a sadistic desire to study maths, physics, and quantum mechanics. This is my long-winded way of saying that Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer is a masterpiece, and I cannot stop thinking about it. The all-star cast is brilliant, and the final scene is as powerful as the Trinity Test. Despite devouring documentaries and critical texts — including Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin’s Pulitzer Prize-winning super-dense, exceptional 600-page biography American Prometheus (which took the authors 25 years to complete); Trinity, Louisa Hall's brilliant historical novel; and Jon Else’s excellent 1981 documentary The Day After Trinity — the impact of the final scene affected me in a way I was not expecting. I cannot wait to see it again.

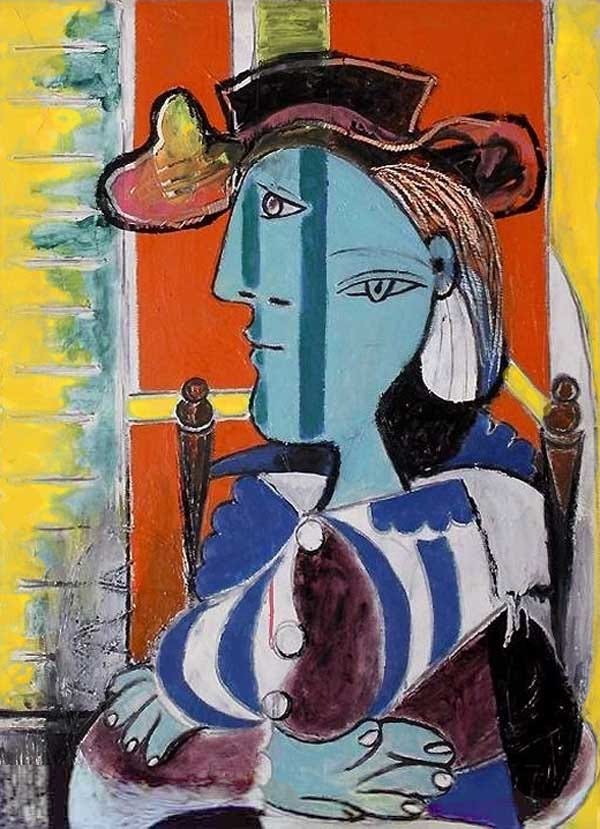

Early in Oppenheimer, J. Robert Oppenheimer (played by the always fantastic Cillian Murphy) walks past various Cubist works of art in an anonymous museum. He stops when he reaches Pablo Picasso's 1937 painting, Woman Sitting with Crossed Arms (sometimes referred to as Marie-Thérèse Walter with her arms crossed), pausing to admire the work. Oppenheimer's childhood home in New York had an extensive art collection, including works by Rembrandt van Rijn, Édouard Vuillard, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, and Vincent van Gogh. As Bird and Sherwin noted in their excellent biography, there was also Picasso — Mother and Child (1905), from Picasso's Blue Period — was also in the Oppenheimer home.

It is a brief scene that stayed with me for many reasons. Before I watched Oppenheimer — when I was reading the books and watching the documentaries — I started to think about references to bombs and science and physics in Surrealism and Surrealist-adjacent artworks and how the connections are there for all to see. While I have seen articles connecting ‘the genius of Picasso’ to the genius of Oppenheimer, I won't be doing that here. I could be obvious and unpack Salvador Dali’s Dalí Atomicus (1948), Uranium and Atomica Melancholica Idyll (1945), Leda Atomica (1949), and his 1954 nod to the Atomic Bomb, but again, that’s too obvious. Instead, I think about André Breton's famous description of Frida Kahlo's art as ‘a ribbon around a bomb.’

As Grace McQuilten writes in their paper, ‘A Ribbon Around a Bomb: Identity and the Body in the Diary of Frida Kahlo’ (Hecate's Australian Women's Book Review; St. Lucia Vol. 14, Iss. 2, (Nov 30, 2002): N/A),

‘he summarised the external perception of Frida Kahlo herself, the constructed self of her artworks, and the impact of her physical presence. Frida was violent, painful, passionate, expressive and dangerous, yet this danger was contained. The potential for her explosion was bound by symbolic ribbons: her costume and masking, her husband Diego Rivera, her self-portraiture.’

The quote about Kahlo was the first that came to mind, but then I naturally thought about Remedios Varo. Varo is often described as a ‘Para-Surrealist’ because of her unique ability to align the natural world with the scientific, the Surreal and the esoteric. The daughter of a hydraulics engineer, Varo was well-versed and educated in scientific apparatus and machines and interested in physics, all of which crept into her artwork. As Lois Zamora wrote in ‘The Magical Tables of Isabel Allende and Remedios Varo’, ‘Varo’s idiosyncratic iconography includes fantastical machines that facilitate metaphysical voyages to other shores, other worlds.’

Varo’s paintings combine the ethereal with the otherworldly and Surrealism with science. Her artworks have a historic quality yet something far-reaching and untouchable, as though only Varo has the means to access what lies — or is waiting to be discovered — on the other side. As Whitney Chadwick writes,

‘Like the Surrealists, Varo painted women. Unlike them, she painted women as active, creative, sentient beings – artists and travellers, seers, sorceresses and scientists. As in the writings of Breton, these women have a special purchase on extra logical truth. They are at home with nature and in touch with the spiritual. But they do not exist only for men; they are busy with their personal explorations.’

Phenomenon of Weightlessness (1963) is especially significant to Varo’s interests in physics, explicitly referencing ‘both Newtonian and Einsteinian theories of gravity at the very moment of radical epistemological rupture.’ We see a scientist slightly tilted, off balance, one foot in front of the other, each one in a different spatial plane. To quote from Natalya Frances Lusty’s brilliant paper, ‘Art, Science and Exploration: Rereading the Work of Remedios Varo’ (Journal of Surrealism and the Americas 5:1-2 (2011), 55-76):

‘A selection of orreries have been neatly placed on shelves, but an orrery of the earth and the moon has broken free of its stand and floats weightlessly into a fourth dimensional space within the room. The fourth dimensional space has been superimposed at an angle of thirty degrees over the original, illustrating the curvature of space-time in Einstein’s theory of relativity. The phenomenon of weightlessness ascribed to free-falling bodies was the germinal seed for Einstein’s development of the theory of gravity—not as a force acting between bodies, but the consequence of the curvature or warping of space-time geometry.’

In 1968, when Peter Bergmann published The Riddle of Gravitation — one of the first introductory works on the evolution of Einstein’s theory of relativity — Varo’s Phenomenon of Weightlessness graced the first edition’s cover.

Science also influenced the sartorial side of Surrealism, and Elsa Schiaparelli is hugely significant in this respect. I wrote about Schiap’s Zodiac Collection for paying subscribers in February 2023 and the influence of the couturier’s Paternal Uncle, Giovanni Schiaparelli. G. Schiaparelli, the Director of Milan’s Brera Observatory, was a reputed scholar of Mars and its comets best remembered for discovering the Red Planet’s water canals in 1877. The Various lunar and planetary discoveries named after him include:

The main-belt asteroid 4062 Schiaparelli (named on 15 September 1989).

The lunar crater Schiaparelli.

The Martian crater Schiaparelli.

Schiaparelli Dorsum on Mercury.

The 2016 ExoMars' Schiaparelli lander.

Also in February I wrote about the Cosmos of Helen Lundeberg, a painter whose work during the 1950s and 1960s focused on interiors, still-life planetary forms, and intuitive compositions. The painter Roberto Matta once said Albert Einstein ‘was as important as Freud to the modern artist, and filled his pictures with geodesic space-time grids like those now used to illustrate black holes and wormholes.’ His painting The Vertigo of Eros (1944) is a testament to this. As MoMA’s website states, ‘The Vertigo of Eros evokes an infinite space that suggests both the depths of the psyche and the vastness of the universe.’

‘A galaxy of shapes suggesting liquid, fire, roots, and sexual parts floats in a dusky continuum of light. It is as if Matta's forms reached back beyond the level of the dream to the central source of life, proposing an iconography of consciousness before it has hatched into the recognizable coordinates of everyday experience. There is a sense of suspension in space, and indeed the work's title relates to Freud's location of human consciousness as caught between Eros, the life force, and Thanatos, the death wish. Constantly challenged by Thanatos, Eros produces vertigo. The human problem, then, is to achieve physical and spiritual equilibrium.’

Although not reviewing Oppenheimer or writing about the film per se, I am still endeavouring to trace the movie back to the artists I love, as I connect some dots between science and Surrealism, physics and ParaSurrealism. Breton's quote about Frida as ‘a ribbon around a bomb.’ Varo's key unlocking access to physical worlds yet to be decoded and discovered. And fundamentally, Twin Peaks: The Return, Part 8.

About halfway through Twin Peaks: The Return, Part 8, a gorgeously filmed, incredibly scored black and white segment takes us to White Sands, New Mexico, 16 July 1945 and the Trinity Test. It was an extraordinary episode of the time and remains stunning now, even more so having watched Oppenheimer (incidentally, both share the same production designer, the brilliant Ruth De Jong). In Twin Peaks: The Return, Part 8, the Trinity Test instigates a Surreal, black-and-white horror film, opening a portal where sinister, dark, terrifying evil entities can no longer return, much like the bomb signalled the start of the Cold War and the atomic age. Sometimes keys should not unlock doors. A ribbon can disguise a weapon’s exterior but is still a bomb.

Love Remedios Varo!