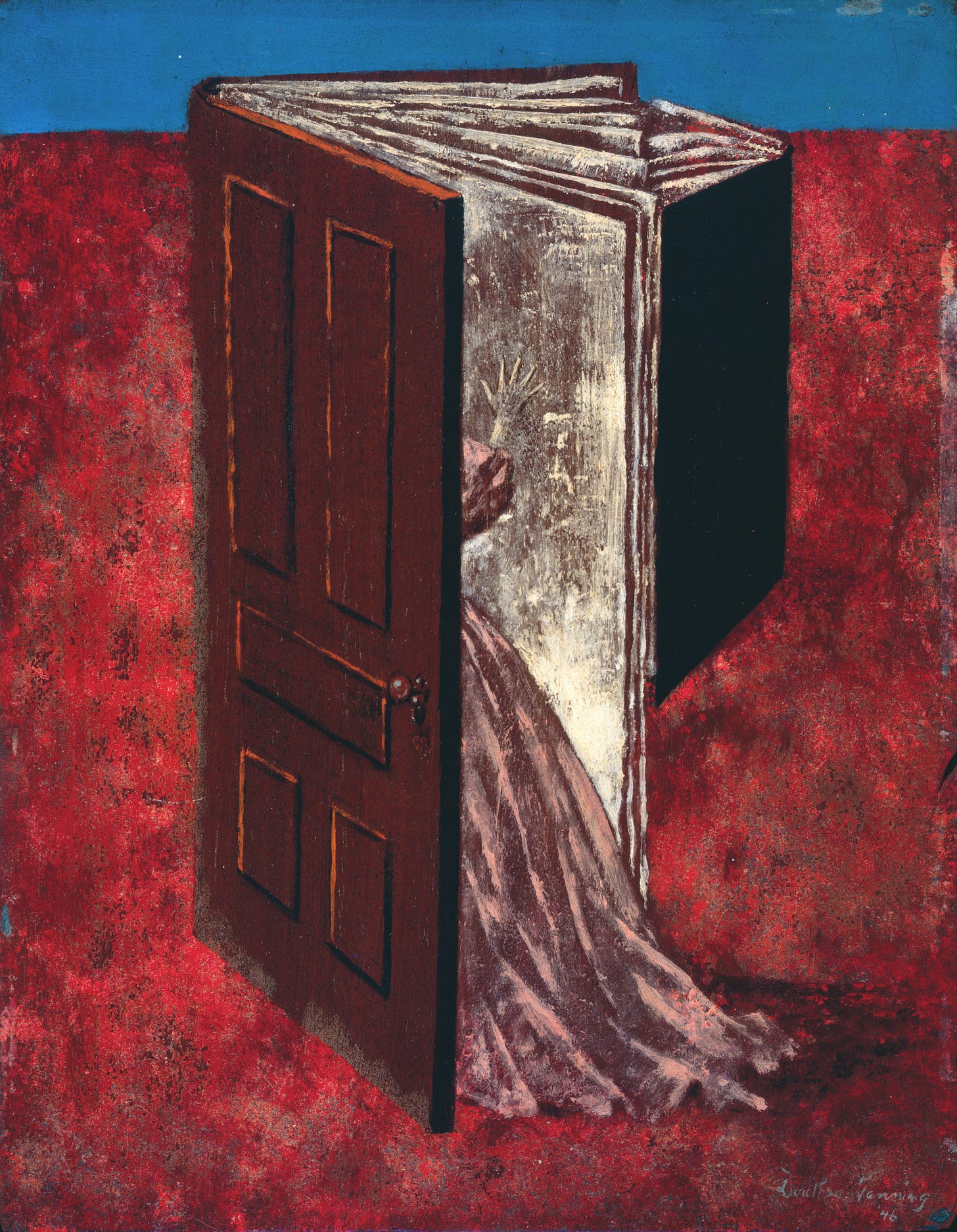

My work is about leaving a door open to the imagination so that the viewer sees something else every time.

— Dorothea Tanning.

I have been thinking about Dorothea Tanning’s work, and Eine Kleine Nachtmusik (1943) has been on my mind. Tanning's feminist-Surrealist art opens doors into girlhood, adolescent sexual awakenings, unsettled psyches, and the disruption of personal and psychological spaces. She takes us to places others would deem taboo but essentially have existed inside us since childhood, where they have remained for our entire lives.

At night one imagines all sorts of happenings in the shadows of the darkness. A hotel bedroom is both intimate and unfamiliar, almost alienation, and this can conjure a feeling of menace and unknown forces at play. But these unknown forces are a projection of our own imaginations: our own private nightmares.

— Dorothea Tanning.

Tanning painted Eine Kleine Nachtmusik in Sedona, Arizona, where she resided in the 1940s with Max Ernst. One of the four doors is slightly open, offering a glimpse into Tanning's mindset and creativity during this time. The juxtaposition of the dreamy and the danger adds to the painting’s potency; two young girls appear caught in a whirlwind, their clothes unravelling and hair caught by the wind. The gust coming from Sedona could also be responsible for the monstrously large sunflower, partially plucked and de-rooted (we can see two of its petals on the bottom right of the painting, while one of the girls holds the third). It is an image that becomes increasingly disquieting the deeper you look into the vortex; it is a painting about lost innocence, the darker sides of childhood and the psyche, and the uncontrollable entities that could invade any situation.

She once described Eine Kleine Nachtmusik as follows:

It's about confrontation. Everyone believes he/she is his/her drama. While they don't always have giant sunflowers (most aggressive of flowers) to contend with, there are always stairways, hallways, even very private theatres where the suffocations and the finalities are being played out, the blood red carpet or cruel yellows, the attacker, the delighted victim…

— Dorothea Tanning.

I love Tanning’s description of ‘very private theatres,’ and the privilege of being offered a glimpse into someone’s life and creativity. Doors are portals into the theatre of privacy, and by opening and walking through them, we essentially fall down the rabbit hole and into Tanning’s world. As Paula Lumbard writes, ‘Dorothea Tanning explores female nature. She takes the cycles of female evolution and reveals them as they really are - multilayered experiences of anxiety and joy, fraught with the female condition she covets, a “mad laughter”.’ The personal becomes public, as we witness the goings-on taking place in private domestic or residential spaces, or, on this occasion, what was occurring in Tanning's life during that particular time. To quote Katherine Conley, ‘Tanning’s paintings redefine domestic space for young women as claustrophobic, haunted by malevolent spirits: “we are waging a desperate a desperate battle with unknown forces”’.

I wanted to lead the eye into spaces that hid, revealed, transformed all at once and where there would be some never-before-seen image as if it had appeared with no help from me.

— Dorothea Tanning.

So many of the themes established in Tanning’s work started in 1942 when she painted Birthday, her best-known self-portrait. She stands with her left hand poised on the doorknob, either just arriving or about to leave, with a serene, calm expression on her face. A wide-eyed winged lemur, an animal associated with nighttime and the spirits of the dead, lies at her feet. Multiple doors are open behind her, and her outfit, what looks like twigs and foliage, but on closer viewing consists of numerous tiny interlocked women’s bodies, is clasped at the waist by her hand. In the words of renowned Surrealist scholar Whitney Chadwick, ‘the doors usher the viewer into her “elsewhere,” a hidden world of fantasy and obsession. But behind the doors in Birthday lies emptiness; poised on the edge of the future, at the juncture between art and life, the artist confronts the possibility of the void.’

There is movement in the image, as there is movement in Eine Kleine Nachtmusik, and there was movement in Tanning's life at the time. She was 32 and deciding what to exhibit in Peggy Guggenheim's groundbreaking 31 Women exhibition at her Art of the Century Gallery when Max Ernst visited her. The echo of uncertainty, of not knowing which door to walk through, is evidenced in her following recollection:

At first there was only that one picture, a self-portrait. It was a modest canvas by present-day standards. But it filled my New York studio, the apartment’s back room, as if it had always been there. For one thing, it was the room; I had been struck, one day, by a fascinating array of doors—hall, kitchen, bathroom, studio—crowded together, soliciting my attention with their antic planes, light, shadows, imminent openings and shuttings. From there it was an easy leap to a dream of countless doors. Perhaps in a way it was a talisman for the things that were happening, an iteration of quiet event, line densities wrought in a crystal paperweight of time where nothing was expected to appear except the finished canvas and, later, a few snowflakes, for the season was Christmas, 1942, and Max was my Christmas present.

— Dorothea Tanning.

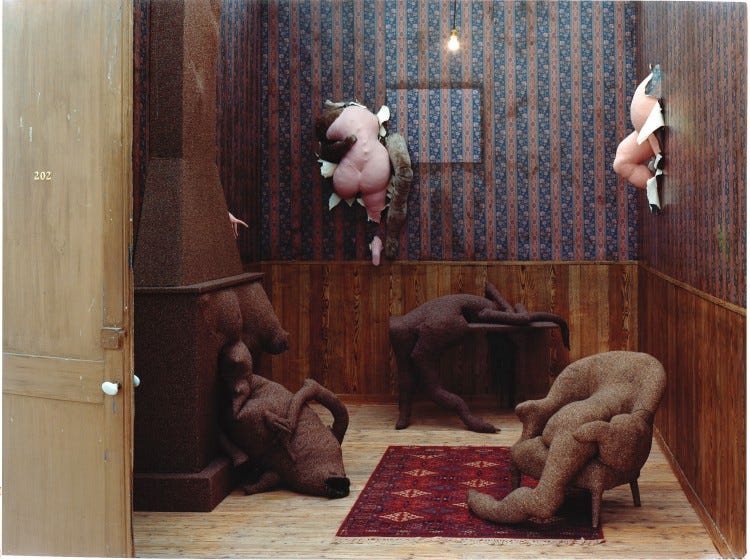

Tanning painted other works featuring doors during her years in Sedona, including Palaestra (1949) and Interior with Sudden Joy (1951). The domestic is always reoccurring in Tanning's work — including in her gorgeously sensual Hôtel du Pavot, Chambre 202 (Poppy Hotel, Room 202) (1970-73) where soft sculptures of women’s torsos protrude from ripped walls. The installation consists of materials including fabric, wool, synthetic fur, cardboard, Ping-Pong balls, and, of course, an open door. As Katherine Conley stated, ‘Tanning’s paintings redefine domestic space for young women as claustrophobic, haunted by malevolent spirits: “we are waging a desperate a desperate battle with unknown forces”’. 1942’s Children’s Games has similar motifs. In the provocative painting, young girls alluding to ‘Alice in Wonderland’ pull the paper off walls to expose more flesh and orifices underneath as their hair and bodies get sucked into the fissures. A third girl lies on the floor; only her lower body is visible. An opening, likely a door, can be seen in the background.

....I read somewhere that what I believed to be poetic and sublime testimonials of my conviction that life is a desperate confrontation with unknown forces are in reality cute girlish dreams, flaring with sexual symbols...

— Dorothea Tanning.

In an interview for BOMB magazine in 1990, Carlo McCormick asked Tanning, ‘There’s a quote of yours—”masterpiece, disasterpiece.” That was a perfect way to describe the brooding violence that runs through your work. Where is that psychosexual aggressiveness coming from?’

Tanning gave the exquisite answer:

That’s a good question. I wish I knew. I don’t know where it comes from. It’s just the way I am and the way I’ve thought all my life. I did a lot of reading. I’ve always been drawn towards esoteric phenomena: the illogical, the inexpressible, the impossible. Anything that is ordinary and frequent is uninteresting to me, so I have to go in a solitary and risky direction. If it strikes you as being enigmatic, well, I suppose that’s what I wanted it to do.

— Dorothea Tanning in BOMB Magazine, 1990.

Thank you for reading. If you wish to upgrade to a paid reader, you are welcome to do so. Or you can buy me a coffee.

Really enjoyed this x