Endgame

Dorothea Tanning, Eve Babitz, & The Queen's Gambit

I often wonder what to write about in these newsletters. I have so many potted ideas jotted down in the form of notes scribbled down in jotters, written on post-its, and even on my phone. I could fill a book with essays I have started and abandoned, or pieces failed pitches. Never wanting to rein myself in creatively, I often have ideas that don’t ‘fit’ certain publications so instead of writing them for myself I drop the idea. Until now.

This essay is one of those ideas.

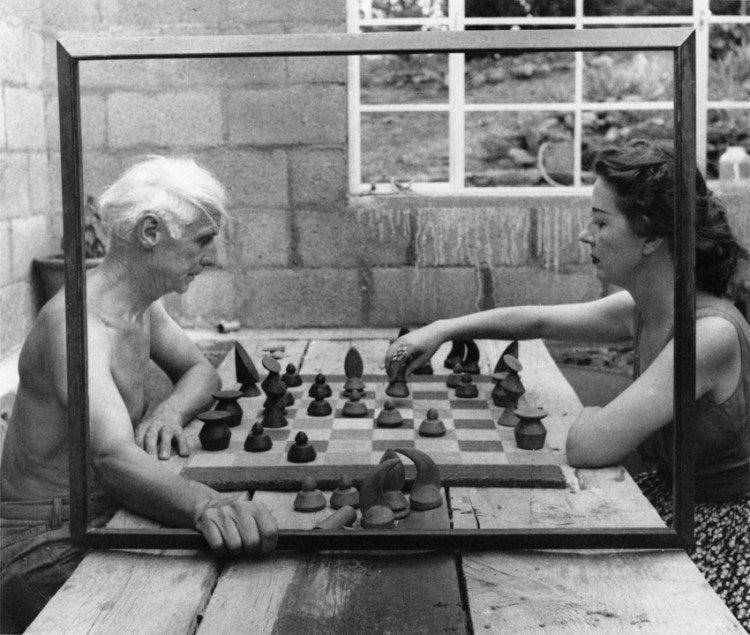

In 1948, Bob Towers photographed the Surrealist artist and writer Dorothea Tanning playing chess with her husband, fellow artist Max Ernst. Taken at their home in Tucson, Arizona, the image depicts the couple mid-play: Tanning's arm is outstretched as she moves her piece, while a shirtless Ernst looks on.

Tanning had a spellbinding relationship with chess because it represented her relationship with Ernst and her association with Surrealism. As the programme for Tate London's 2019 Tanning retrospective emphasised, 'the game of chess represents intellectual and artistic interplay with members of the surrealist circle, as well as her romantic link with Ernst.'

The photo was not the first, or last, time chess would appear in a Surrealist context. Let's take a brief detour. Fifteen years later, in 1963, Julian Wasser captured a very different game when he immortalised the writer Eve Babitz, at the time a twenty-year-old Los Angeles Community College student, playing chess with Dada artist Marcel Duchamp. Babitz famously appears naked, while Duchamp is fully clothed. Babitz talks about this photograph in her article 'I was a naked pawn for art' that appeared in Esquire's September 1991 issue and later included in her brilliant essay collection I Used to Be Charming. With her usually self-referential, brilliantly insightful, and typically Babitz way, she candidly discusses her body and the photograph while defusing the larger myth that she has fallen prey to male (Surrealist) artists objectifying the female body in their art.

“Of all the things that have ever gone on between men and women, this was the strangest, in my experience. But it got stranger. For one thing, there were Teamsters in the next room, moving paintings, and they couldn’t help but be amazed.”

I'll return to Babitz another time, but, for now, let's come back to Tanning.

Four years before Towers' photograph, Tanning painted her vivid, exciting Endgame (1944), a unique, dazzling work where a large, white high heeled shoe takes on the Queen's role to dominate the game. Visually similar to the white stilettos Meret Oppenheim served up on a silver platter in her iconic sculpture Ma Governess (1936), Tanning's white shoe is a bold, powerful display of the Queen crushing the Bishop. Meanwhile, underneath the game in play, the bottom corner reveals blue skies and luscious rolling green hills symbolising the sprawling Arizona landscape Tanning and Ernst retreated to during warm summer months.

Speaking to Artnet in March 2019, the art historian, author, and curator Alyce Mahon (who co-curated Tate's Tanning exhibition) said, "it is as if the chessboard has been ripped open and you have a landscape where the Queens is going to run away to." The painting signifies wanderlust and a desire to escape. Painted before Tanning's divorce from her husband and Ernst's split from Peggy Guggenheim, the image symbolises a ripping apart of conventions. As Mahon continues, "Tanning and Ernst were spending summers in Arizona until they could marry and cohabit. As bohemian as they were, cohabiting [before marriage] was still frowned upon." Wasser's photo is almost like an unspoken, silent, or telepathic conversation between the couple as they communicate through the game. Tanning perceived intimacy and sensuality in chess that most people fail to see — she described it as 'close to the bone.' "I think that's lovely," Mahon relayed to Artnet, "if you think of two lovers passing pawns between each other."

I kept thinking about Endgame, Tanning, and the Surrealists association with chess as I watched the Netflix series The Queen's Gambit. Starring Anya Taylor-Joy and based on Walter Tevis' novel of the same name, the cold-war set miniseries focuses on orphaned chess prodigy Beth Harmon as she grabbles with her brilliant talent and spiralling self-destruction.

Raised in an orphanage after her mother's death, the establishment is both the catalyst of Beth's genius and her subsequent reliance on tranquillisers. Night after night, the young girls queue to receive two pills, one green, one red, in the guise of "Vitamins" from the dispensary. Beth's friend Jolene (Moses Ingram) advises her to save the green ones before bed "otherwise they turn off right when you need them to turn on."

During this time, Beth's learns chess, hones her prowess, realises she can practice her moves by visualising and playing a game in her head. Self-medicating with handfuls of pills only heightens the lucidity of her game, and she is soon forgoing sleep to lie awake, picturing the board and the moving pieces on the ceiling above her bed. People are continually perplexed when Beth informs them: "I play chess in my head; on the ceiling."

These scenes are vivid, dreamy, hypnotic, allowing Beth to 'see' how she can win. Yet she becomes increasingly reliant on the little Xanzolam pills that enable her to relax her mind and hone her thinking. Beth's chemical dependency made me think about how artists' dependencies on drugs to inspire, offer clarity, and clear the cobwebs in search of inspiration. It also brought to mind the parlour games the Surrealists would play, usually heightened with drugs, the artistic technique of automatism and automatic writing.

Automatic writing, where artists suppress conscious thought to create, was responsible for some of Surrealism's best-known works. Phillipe Soupault and André Breton wrote 1919's Les Champs Magnétiques (The Magnetic Fields) in a state of unconscious thought, and in 1933 Breton wrote The Automatic Message, his most famous article on the subject. Yet automatism was not restricted to writing and was used by a variety of Surrealist artists. One of the best-known examples was André Masson, who adapted the automatic writing process to his art. Masson's methods included depriving himself of sleep, meals, and experimenting with drugs to increase spontaneity and lessen control over his canvas. In The Queen's Gambit Beth is not so much engaging with automatic chess, but the clarity she achieves to 'create art' through the game is somewhat similar.

The above photo by Lee Miller, Portrait of Space (1937), has been National Galleries Scotland as Miller's best-know Egyptian image and one that 'transforms the desert view through a torn fly screen door into a dream-like, Surrealist, space.' The creation of a tear to look outside your surroundings reminded me of the moment an older Beth rips the canopy above her bed because it obscures her view of the ceiling. By creating the slash in the fabric, she can resume her imaginary game. At that moment, Beth has developed a disruption similar to the trompe l'oeil detail in Miller's picture, but more similar to the one in Tanning's Endgame. Tanning frequently explored the domestic space in her art — doors open, canopies are ripped, soft bodies emerge and disappear into walls. Imaginary games are played, and canonically 'female' symbols (including homes and nurseries) are dismantled and disrupted, creating pathways to sexual liberation and new worlds. Breaking open her canopy, enables Beth to escape from her past, and enter a new world.

In 1989 Roland Hagenberg would ask Tanning about chess for his article "Dorothea Tanning," Art of Russia and the West. An extract of this appears on The Dorothea Tanning Foundation's website, underneath her painting of Endgame. Her answer is fascinating, revealing her character's determination, the critical thinking of her mind, and her survival instinct as an artist. It is an answer that could apply to Beth Harmon.

Hagenberg: What is the obsession with chess by artists of your generation?

Tanning: It's more than a game. It's a way of thinking. You have to be clever in a warlike way. You are a good chess player if you have a mean streak in you. I think mean people make good chess players.

Hagenberg: Is that the way you find out about other people?

Tanning: No, but it's only that people who are too sweet cannot learn how to play chess.

Love Letters During A Nightmare is a series of newsletters by me, Sabina Stent, about things I adore. It’s free (for now), by if you enjoyed and would like to buy me a coffee/contribute to my research fund, you can do so via my Ko-Fi Page. If not, please subscribe via the button below. Thank you for reading.