Jane Graverol

I’ve always loved Jane Graverol’s work; she is an artist I think about all too frequently, and I was lucky enough to see one of her pieces—maybe my favourite of hers—at an exhibition this week (stay tuned for a forthcoming newsletter). But for now, I wanted to write a little for those of you less familiar with this Belgian Surrealist.

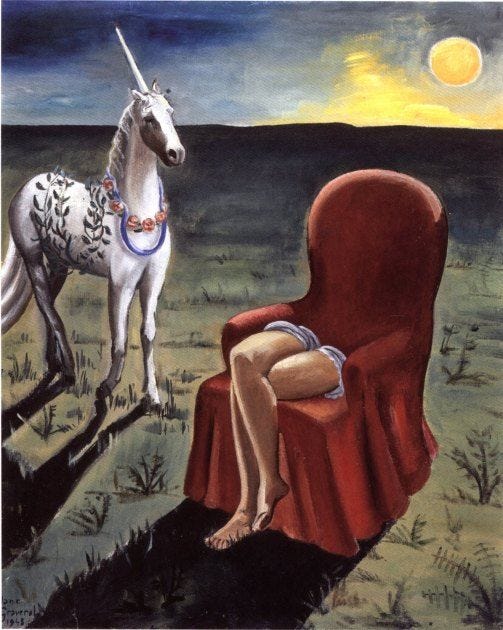

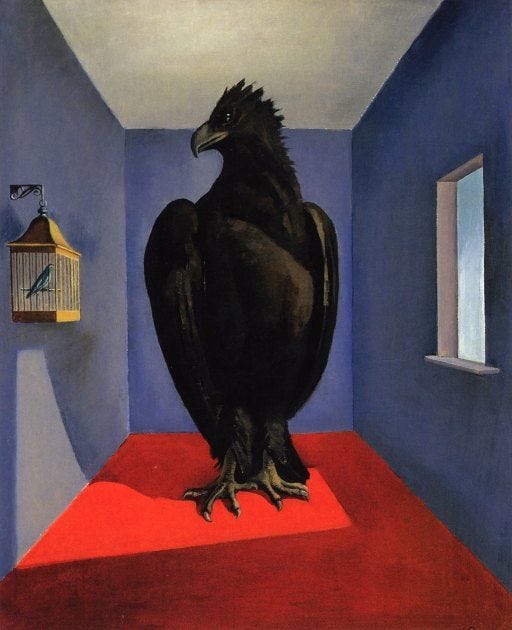

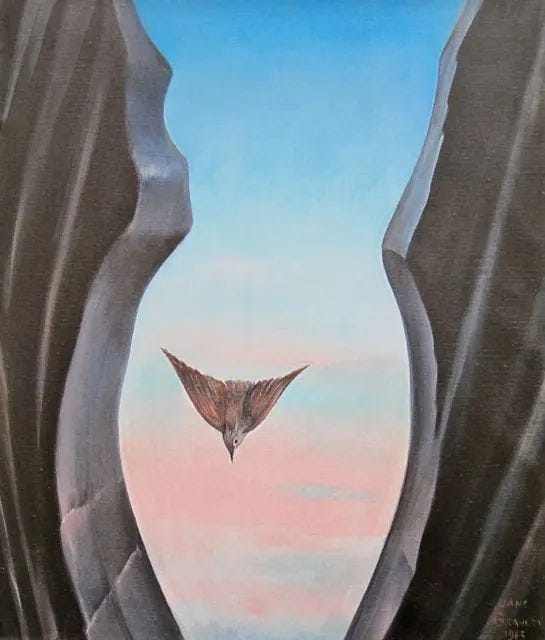

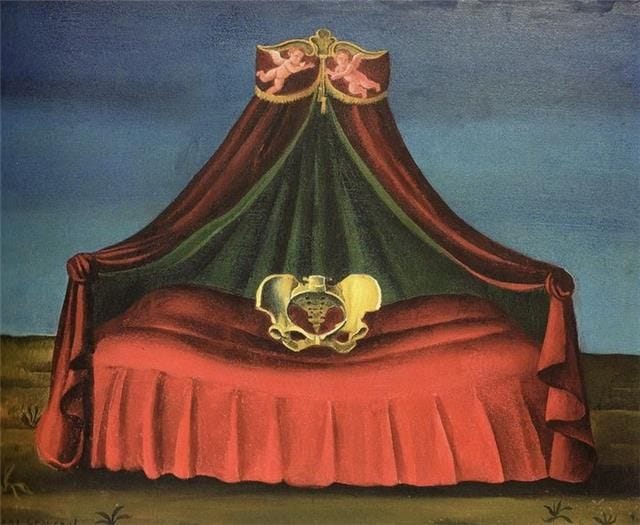

Jane Graverol (1905-1984) somehow combines elements of my other favourite artists: she explores girlhood like Dorothea Tanning, maps the organic terrain of the female form like Ithell Colquhoun, was unabashed in her sexuality like Leonor Fini, provokes the domestic like Gertrude Abercrombie, channels mysticism like Leonora Carrington, considers technology and mythology like Remedios Varo, and explores botany like Helen Lundeberg. But her work is unmistakably Graverol’s, or, as she described her canvases, “waking, conscious dreams”. Winged creatures—angels, birds, butterflies, and more mystical creatures like phoenixes or dragons—appear in many of her paintings, and while her work is mythical, it often features a mechanical element, with women and machinery working together to achieve pure freedom without constraints.

Born in 1905, Ixelles, Belgium to a family of artists (her father was painter Alexandre Graverol), Graverol enrolled at the Academie des Beaux-Arts of Brussels in 1921, where her teachers included Constant Montald and Jean Delville. While she is usually associated with Surrealism, Graverol was already a working painter prior to this association: she had started exhibiting her work in 1927, when she was still working in a more symbolist fashion, before her trademark style took hold and before the movement’s ascention.

Strongly influenced by Rene Magritte, who she first met in 1949, Graverol was key to the emergence of Surrealism in Belgium and her painting La Goutte d’eau is a collective portrait of the Belgian surrealists. She created the magazine Temps mêlés in Verviers in 1953 with André Blavier, and met Marcel Mariën the same year. The pair were together for a decade, living and working together on the magazine Lèvres Nues, and in 1959 released L’imitation du Cinéma. The film, with its themes of eroticism and anticlerism, was banned on release. During the 1960s and 70s, as the popularity of Surrealism waned, Graverol turned to social collages focusing on violence and war. Her work also turned to the natural world, painting small-scale works of animals, flora, and fauna.

I’ve read that her vision of Surrealism offers “an original, dreamy version of feminine sensibility in painting, served by a figurative technique that was both precise and cold”. I don’t consider it cold. I think it’s brimming with sensual energy—alive, potent, tactile, and unmistakably Graverol.

These winged creatures, these dragons and angels, would form part of her later collages; a consistent thread throughout her work. To quote a blurb from La Biennale di Venezia 2022,

“taking the ambiguity of the mythological to an extreme, she [Graverol] conveys a femininity that is monstrous, yet aware of its own sensuality. Though her insides are a tangle of machinery, her face is as delicate and seductive as the flower held in her paws. Refusing to consider this vanity a flaw, Graverol presents it as an essential tool for the modern woman, and sees this interweaving of mythology and technology as the way to emancipation. This metamorphosis into a hybrid yields the image of a female figure who can mould her own destiny by turning the parts of her body into weapons of social empowerment.”