I had lots of fun talking about Yellowjackets, women Surrealists, and the antler queen at BAFTSS Horror Studies ‘No Return: A Yellowjackets Symposium’ last weekend. So, I thought I would post the paper here for the curious subscribers amongst you. Enjoy!

There’s a moment in the penultimate episode of Yellowjackets season one, when we finally see Lottie don the headdress and claim the crown of the antler queen. While this much-anticipated reveal confirmed one of the show’s more popular early fan theories, the sequence — which took place during the fantastically trippy mushroom scene — amalgamated many elements of what makes Yellowjackets so appealing and exciting to viewers: feral young women, the unexplained and unpredictable, the potential cannibalism we have been teased since the opening scene, feminine wildness, and animalism.

Throughout the show, and especially now considering the shocking end of series cliff-hanger, I have been fascinated by Lottie. From her psychic experiences as a child, her spiritual rebirth (or baptism), to what I call her decent into the darkness when Laura Lee died, and finally taking on the mantle of the antler queen, Lottie has stepped into her power as Yellowjackets progressed. More specifically, I have been struck by Lottie’s similarities — whether artistically, personally, and even sartorially — to horned female deities as captured by women Surrealists, including Leonora Carrington, Remedios Varo, and Leonor Fini. What these artists, as well as Yellowjackets, did so well was revert the art movement’s patriarchal symbol of the Minotaur, and it’s dominating emblem of masculine superiority and female suppression, by transforming it into one of innate female power, magic, and transformation.

In this paper, I will be (briefly) explore Lottie’s connection to the antler queen alongside women Surrealist artists. Looking to the show, as well as art and the uncanny, I hope to show how Lottie, a young woman with a keen sense of intuition, or psychic ability, who can see things outside the boundaries of ‘our world,’ shares similar characteristics to some of the most significant women in modern art. Sartorially, I also wish to consider how Lottie’s horns became her armour, something that has reflected in the well-known fashion magick of Leonor Fini.

I’m going to begin by showing a couple of examples by some very well-known male artists in order to demonstrate how women shifted the narrative away from submissive female bodies violated by men, to autonomous and powerful horned female deities and entities.

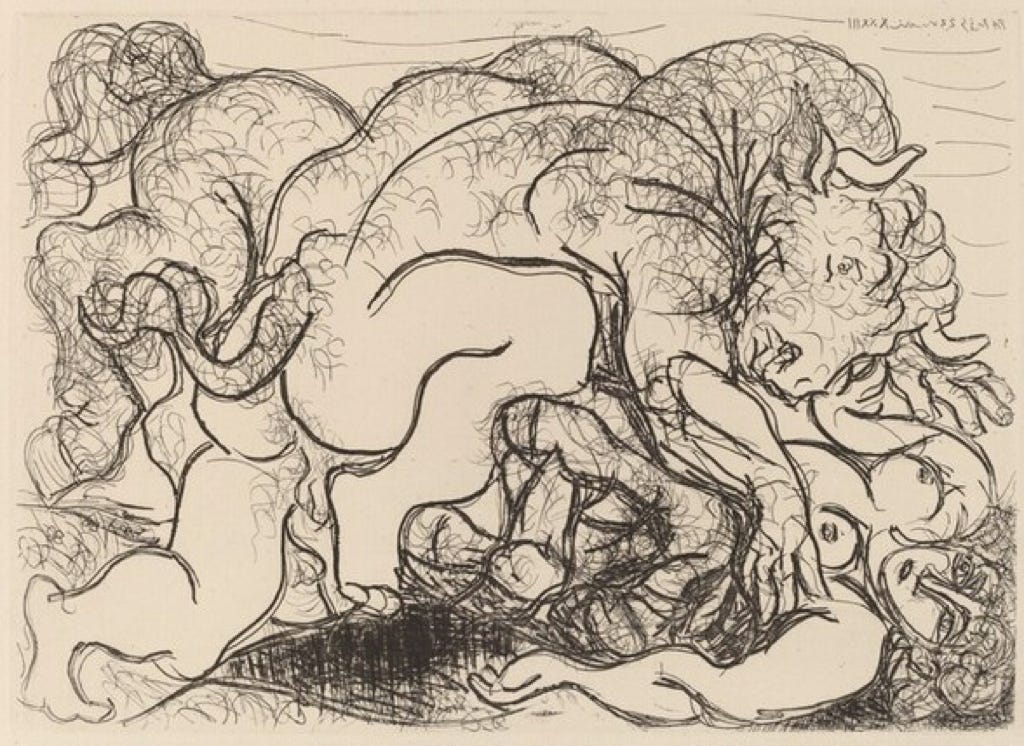

There is a well-known Picasso painting titled Minotaur Ravishing a Female Centaur (Minotaure amoureux d'une femme-centaure), state III, from the Vollard Suite (Suite Vollard) 1933, published in 1939.

The MoMA website describes the painting as so:

The mythical Minotaur—part man, part bull—was Picasso's alter ego in the 1930s and part of a broader exploration of Classicism that persisted in his work for many years. The Minotaur was also emblematic for Surrealists, who saw it as the personification of forbidden desires. For Picasso it expressed complex emotions at a time of personal turmoil. The Minotaur symbolized lasciviousness, violence, guilt, and despair.

Appearing frequently throughout a range of Surrealist works, the horned, dominating beast retained and reinforced the misogyny that ran throughout the movement. The group’s literature journal, which ran from 1930 – 1939, was even named ‘Minotaure’, and in 1934 featured images of Hans Bellmer’s notorious sexually explicit dolls.

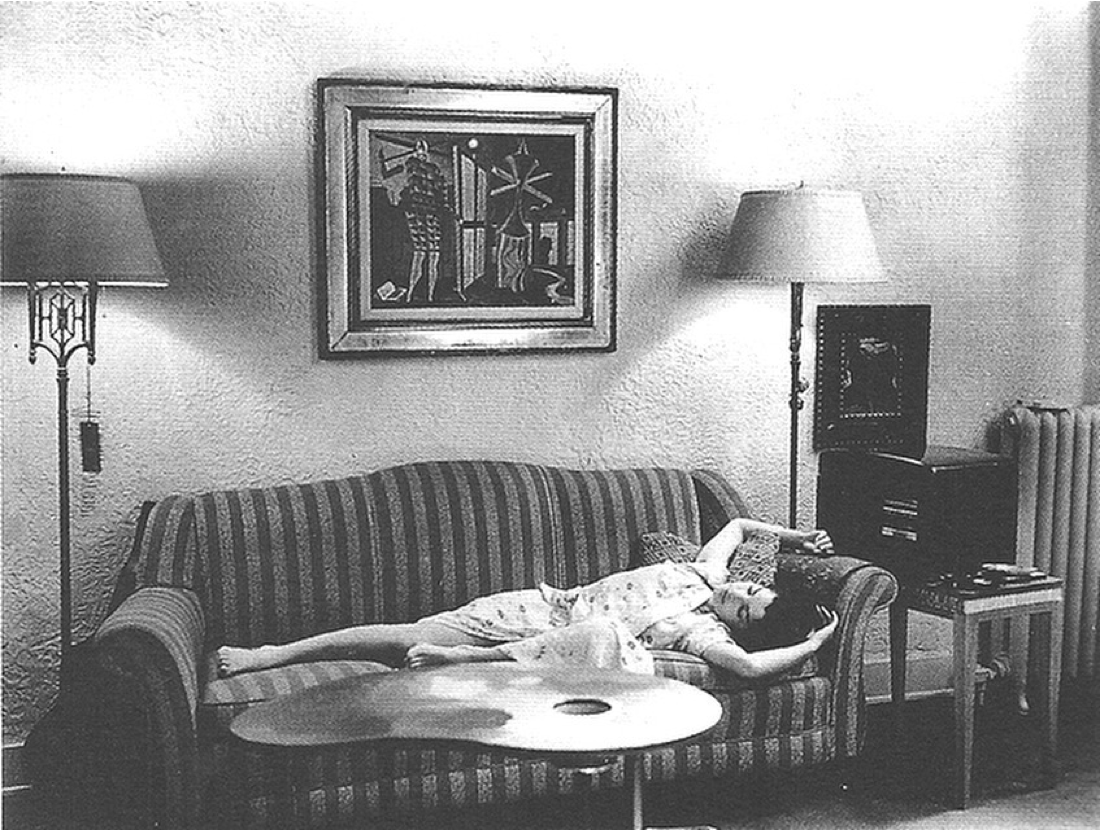

In 1945, Man Ray painted his partner Juliet Browner — the couple married in Los Angeles the following year — in the repose of the Minotaur in his Vine Street studio in Hollywood. Browner can be seen on the couch, arms bent to her side, one leg bent. Rather than being dominated by the minotaur, she has transformed into one herself, occupying a once-masculine space.

As more women became active in the Surrealist movement, they actively explored and reimagined male dominated subjects. In 1959, the Spanish Mexican Surrealist artist Remedios Varo painted Minotaur a cosmically blue feminine horned creature. Known for her androgynous, alien figures with oval faces and almond shaped eyes who more than resembled the artist herself, Varo’s appeasing yet magically inhabited protagonists always disarm any preconceived threat, or strangeness because of who, or what, they resemble. In Minotaur, the figure encourages her spectators, or guests, towards her by way of a friendly greeting.

Varo’s Minotaur is both human and not human; thin legged, delicate, divine, she is dressed in form-fitting cross-stich. She is surrounded by the hood of a shimmering cloak, and, significantly, small white horns curve upward from each side of her head. Varo, furthermore, has painted a tiny galaxy instead of a crown of hair. There’s a great paper titled ‘Horns of the goddess: The Minotaur in the work of Varo, Carrington, and Lam’ where the author (who is uncredited) states, describes the work as ‘a cosmos in which gossamer clouds of a blue-white material float upward, anchored by a small glowing orb in the center [sic].’ We can also see a gold key in her elegant hands. The author also goes on to say:

Though ordinarily seen as a symbol of the masculine, this bull’s horns are moon shaped, a symbolic link to the possibility that “the bull can also be as a lunar symbol, when ridden by a moon goddess. In this context the bull usually has the meaning of the taming of masculine and animal nature” (Bull,” 2001, para. 2 cited in ‘Horns of the goddess: The Minotaur in the work of Varo, Carrington, and Lam’).

The mention of a horned bull allows me to spin-off into a brief aside about the Italian-Argentian artist, and a personal favourite of mine, Leonor Fini.

Self-governed, powerful women who only answered to the cat god — much like the artist herself — are the crux of Fini’s work, and never more so that in her personal sartorial style where she inhabits the role of what I call a fashion magick sorceress. Fini had a great amount of pleasure in costume and dress, and every year would spend late summers at a monastery in Nonza, Corsica, to coincide with her birthday.

Friends would arrive, and photographers including Eddy Brofferio would document the occasion. In the words of her biographer Peter Webb, ‘some of the most beautiful and inspired photographs ever taken of Leonor as muse and sorceress were taken by Brofferio.’

We can also draw on the fashion magick of Alexander McQueen, whose sartorial use of armour, horns, and furs transformed women into powerful warriors. Fashion became battlewear and protection, which Fini knew very well. In taking on the role of the antler queen, Lottie harnesses this energy, this armour, and this power.

While I can see flashes of Lottie in the history of Surrealism, Varo’s art, and in Fini’s channelling of fashion magic, the artist I think is the most significant when discussing Lottie — both personally and in her association to the antler queen — is Leonora Carrington. I’m sure some of you will be familiar with Carrington, the British-Mexican Surrealist who is finally gaining new fans, greater artistic acclaim, and recognition with every passing day.

One of Surrealism’s most enduring works is Carrington’s 1953 painting And Then We Saw the Daughter of the Minotaur, a work where a white Minotaur appears to be holding court at a ceremonial table. Two children can be seen standing in line, a humanoid flower is to her left, and a sprite-like whisp, as if appeared from another realm, dances in the frame. Tendrils weave up columns, and two white hyenas (one resting, one standing) are in the corner of work. Carrington’s art is magical, otherworldly, alchemical.

To quote Siobhan Leddy on the Gallery Wendi Norris page (a gallery with a wonderful array of women Surrealists, including Carrington, Alice Rahon, and Varo), ‘bodies transform into birds or beasts, ghostly figures float mid-air. As viewers, we are more than just witnesses to this magic—we become complicit in it.’

Describing the painting, Leddy writes:

We are offered a seat at the ceremonial table—alongside dogs, children, a minotaur, and a fantastical, almost aquatic-looking creature—in the 1953 work And Then We Saw the Daughter of the Minotaur. Mysterious glass orbs pull at the tablecloth as though guided by a force of their own. At the right of the painting, something not-quite-human dances toward us. No wonder Edward James, Carrington’s friend and patron, once described her work as “brewed” rather than painted.

I love this description of her paintings as ‘brewed’ through magical ceremony. While Picasso’s depiction of the Minotaur was pure male gaze and voyeuristic dominating fantasy, in And Then We Saw the Daughter of the Minotaur, Carrington reworks the mythological narrative. Returning to the paper I mentioned earlier, the author states, ‘it is clear that Carrington is reshaping the mythological narrative in which the archetypal Feminine—represented by the Minotaur’s mother, Queen Pasiphae, and Ariadne, the Princess of Crete—is powerless in the face of masculine forces that are blindly caught in the need to gain power over an adversary.’ Carrington’s minotaur is all governing, all powerful, ceremonial, and magical. Hardly passive, she is in control. Known for weaving Surrealism and magic realms, the tarot and myth, Carrington’s otherworldly visions dated back to childhood when she was visited by apparitions in the form of various animals (cats, wild tortoises, or a horse). When Lottie approached Laura Lee that she is ‘seeing things’ about her visions, Laura Lee tells Lottie, “I was taught that visions are God’s way of communicating. They could either be a warning or a revelation.” “But how do they know they’re not just crazy,” asks Lottie? “They’re evidence of things unseen”, Laura Lee replies. “They knew it because they believed it.”

Madness ripples through Surrealism. In André Breton’s novel Nadja, the self-styled ‘pope of Surrealism’ describes an encounter with a mysterious woman on the streets of Paris (as much as I don’t want to dwell on Breton, I think his inclusion is relevant here). He describes this young woman as mentally unstable, or mad. As he writes in the book, ‘I have taken Nadja, from the first day to the last, for a free genius, something like one of those spirits of the air which certain magical practices momentarily permit us to entertain but which we can never overcome.’ Nadja is neither fully grounded, nor entwined in death, but has an undeniable connection to the uncanny. As she herself says, ‘I am the soul in limbo.’

Lottie’s ability to see the hidden increases along with her power over the course of the series, and this appears to become stronger as season one concludes. What she remains capable of exacting, we still do not know. Lottie is the one who says “follow the stag” in Coach Ben’s direction during the shroom scene, and she is the one who, we could say, castrates the male minotaur by taking on the role of the antler queen. This is the moment we witness Lottie fully in control of her power and command.

This is not the first time Lottie sees a vision the stag. When she is baptised by Laura Lee, Lottie sees and follows a stag up a candle lined staircase. While under water she sees something which Lorelei says is ‘the light,’ but it could also be interpreted as Lottie’s voyage ‘Down Below.’

In 1940 Carrington painted Down Below and in 1943 wrote the book of the same name, both about her psychiatric breakdown and horrendous time in a mental facility. In the latter Carrington writes, “I was transforming my blood into comprehensive energy—masculine and feminine, microcosmic and macrocosmic—and into a wine that was drunk by the moon and the sun.”

We can compare and relate Carrington’s breakdown in ‘Down Below’ to Lottie’s trajectory throughout the series. The blood energy Carrington speaks of, the fusion of power traditionally associated with specific genders, and the alchemical power of the body, links beautifully to the shot of Lottie in the Season 1 finale when she places a bloodied heart into a hollow tree trunk and says the incantation ‘versez le sang, mes beaux amis (shed blood, my beautiful friends) and let the darkness set us free.’

Carrington would harness this trauma and horror into her later work, especially ideas of the alchemical body. I cannot help wondering what further ideas surrounding ‘the alchemical body’ will be explored either by Lottie or in forthcoming series.

So, in conclusion, I hope I have demonstrated in my mind’s eye how Lottie and Yellow Jackets’ Antler Queen can be connected to both women Surrealists and their horned deities, specifically how women artists turned this masculine symbol of violence and suppression into one of innate female power. Light doesn’t exist without darkness, and those labelled madwomen are often the most perceptive, and the most open to mythic and otherworldly messages. Sometimes there is power when accepting the darkness within. There’s a fantastic quote from Fini which I wanted to end with, because I think it’s applicable to Lottie. Fini once said:

“I know that I am related to the idea of Lilith, the anti-Eve, and that my universe is that of spirit…It’s me but not just me; it’s the essence of the feminine. She is the woman, symbol of beauty and deep knowledge. She emerges from the water, the essential element of life, the primeval material, because she knows how to survive the cataclysm.”

Thank you for reading this very long newsletter until the end!

I missed this post earlier but damn this is good