Specific artworks linger in your mind long after you see them. For me, Lee Miller’s Untitled [Exploding Hand] (1931) is one of those images. Taken outside the Guerlain Perfumarie in Paris, a hand appears to combust, sparking, as fingers lightly touch the shop’s door handle by way of entry. The photograph is part sensual, part mystery, part horror film. To me, it’s mesmerising.

The photo plays into a specific fascination of mine: hands and gloves in Surrealist art, particularly Surrealist art by women artists. The blood-red fingernails of a femme fatale. The black-gloved killers of Giallo films. Rita Hayworth as Gilda, peeling off her elbow-length satin black gloves as she sings ‘Put the Blame on Mame’ in Charles Vidor’s 1946 film. The knife wirlding hand in Psycho’s shower scene (and countless other examples). Gloves and hands have a riveting cinematic and artistic connection that fascinates for several reasons, including sartorially and symbolically—desire, eroticism, threat, danger. Hands as tools of both pain and pleasure.

One fine example of hands occurs in the 1939 Surrealist film Un Chien Andalou. Directed by Luis Buñuel, and made in collaboration with Salvador Dalí, there is one pivotal scene where a cluster of ants crawl from the palm of a closely focused hand. It’s a fidgety, squirmy, moment that has been compared to the unconfortable sensation that accompanies sexual yearning and pent-up desire. It was not the last time Dalí attempted to depict repressed hunger on film on-screen through the five-digit appendage. For L’Age d’Or, his next venture with Buñuel, Dalí wanted to present a scene ‘of the man kissing the tips of the woman’s fingers and ripping out her nails with his teeth.’ The moment, much more body horror in tone, was refuted and never filmed.

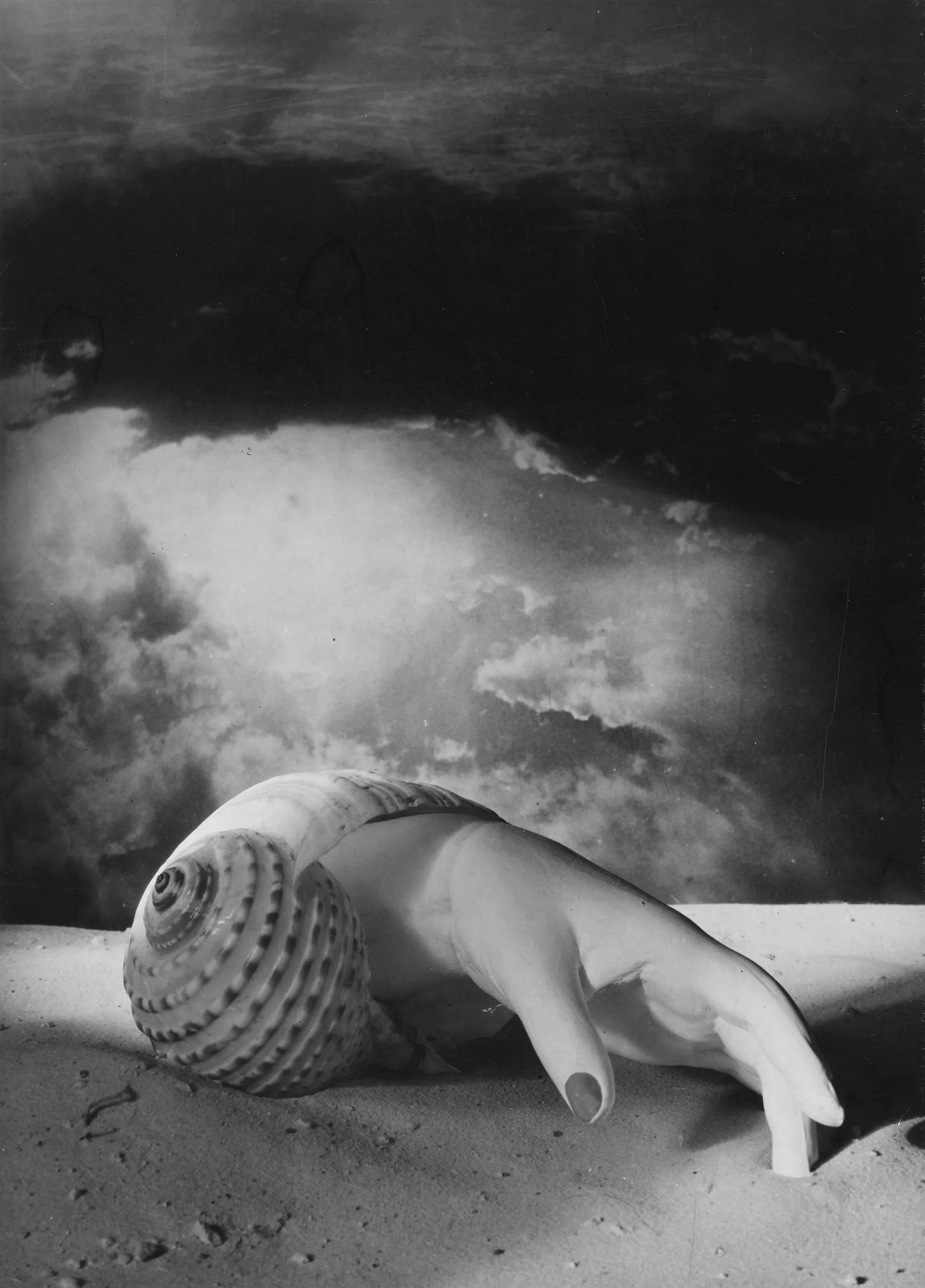

While Dalí wanted to tip the eroticism of hands into the realms of pain, there are other, more alluring, less jarring examples. Dora Maar gorgeously captured the sensuality of hands in her brilliant Untitled (Shell hand) of 1934, another of my most visited and favourite images. A hand — likely from a mannequin (another Surrealist motif) — with fingernails painted blood-red or dark green, which Maar herself favoured. The hand emerges from a large shell on what appears to be a deserted beach, the middle finger teasingly pushing into the sand as clouds gather in the background. It seems a dark and intense storm is about to rain down. The image is beautifully erotic, imbued with self-pleasure and desire, as well as a type of fraught danger. The intensity of female desire, perhaps, and the sizeable power, in this case environmental, it wields.

Once described as ‘sensuous, macabre, bizarre’ by the Surrealist scholar Mary Ann Caws, Maar displayed ‘insipient Surrealist tendencies’ throughout her career. There was also something about the unexpected about her and an element of personal danger. My mind always returns to this astonishing anecdote:

‘Sitting there one evening he [Picasso] saw a young woman peel off her elegant, embroidered gloves, lay her hand on the table with its fingers spread and, like a circus performer throwing daggers, stab between them with a pointed knife. Her aim was poor and everytime she missed she drew blood.’

While some audiences once only knew Maar’s name because of her connection to Picasso, the tide has (fortunately) since shifted, especially within the last couple of decades. In 2009, the writer Alan Taylor described Maar as: ‘far and away the most intelligent woman Picasso had ever met: the only intellectual with whom he ever shared part of his life.’ Maar painted and wrote prose, but it is in her photographic work that she is the most acclaimed. Her work could be bizarre, disorientating, verging on the macabre — and sometimes on the supernatural — but always incredibly fascinating. There’s also something rivetting in a photomontage from 1935, in which a hand appears to “pluck” a mannequin lower torso as it hovers over the Seine. One can’t help wondering: is this the lower torso to which the disembodied hand belongs?

The scholar Johanna Malt has noted that there is no blood and no wound whenever you see hands in Surrealism. In describing this, she states how ‘the body may be cut into pieces in much surrealist imagery, but there is never a wound, for mannequins do not bleed, indeed they incorporate into the very structure of the articulation the possibility of their own disintegration’. Does the deception lessen the impact or only heighten the Surrealist tone?

We see this in movies, too. In The Women, George Cukor’s sartorially forward 1939 comedy, the influence of the Surrealist couturier Elsa Schiaparelli is dominant. In the film’s famous technicolour fashion scene (a sequence Cukor would come to regret), one outfit is seen with a mannequin hand-like brooch. As an aside: five years earlier, Schiaparelli’s April 1934 collection coincided with the May issue of the Surrealist journal ‘Minataure’ and Georges Hugnet’s essay ‘Petite Rêverie du grand veneur’ (Small Dream of the Great Huntsman). The latter was an article illustrated by hands in a variety of poses. These images replicated the tradition of carved hands worn as amulets, and all fingers would be expressing a variety of meanings. These hands were not unlike Schiaparelli’s 1936-37 jewellery modelled on Victorian brooches in the shape of the hand, especially those designed by Jean Schlumberger, who would later become Tiffany’s head designer, who Schiaparelli hired to create a line of costume jewellery. Wearable sculpture made from mannequins: something the Surrealists so excelled.

Returning to perfectly manicured hands, I cannot talk about blood-red fingernails without discussing Meret Oppenheim. Their furry artworks are as notorious for their brilliance as for their weirdness (what camp do you fall into?) A considerable part of Oppenheim’s legacy was toying with the body, external and the internal, anatomical and physical, otherwordly and mortal, masculine and feminine. In doing so, she produced some of the most daring artists of the twentieth century (that’s a story for another time).

Through Fur Gloves with Wooden Fingers (1936), Oppenheim presented furry gloves (not unlike her teacup and bracelet) with elegant wooden fingers and blood-red nails. (Blood of the nail lacquer or blood of a kill?) Like the blood of Maar’s knife wielding-parlour game, or the varnished fingers of her hand emerging from the shell on a beach, Oppenheim has created something familiar yet slightly unsettling. In her Fur Gloves, Oppenheim combined Beauty and the Beast, the real and the uncanny, the pleasure and the pain. It harks back to the potency of hands in Surrealism and the potency of hands. The red nails, the ‘femaleness’ of the image, the elegant fingers. Animalism has taken on an allure and sexual power previously unrendered to it’s greatest effect.

Hands evoke pleasure and pain, the beauty and the beast, the real and the uncanny. Boundaries become blurred, overlap, and intermingle. And when we realise this, we can not stop staring.

Love Letters During A Nightmare is written by me, Sabina Stent, about things I adore, enjoy, and generally have on my mind. It’s currently free to read, but if you enjoyed and would like to subscribe, please do! Also, if you enjoyed and would care to buy me a coffee/help out a freelancer with a one off tip, you can do so via my Ko-Fi Page. Thank you for reading!