Before I ~break~ (because do freelancers ever really break?) for Christmas, I want to thank everyone who has read, subscribed, supported, attended one of my talks, Tweeted, or said kind things about my newsletter, my work, or about me (let’s be honest, I’m a Leo who loves compliments). I’m very grateful, and it’s always encouraging when readers say they enjoy what I write over here. Today's piece is my spin on a very popular new release.

This week, I watched Guillermo del Toro’s beautiful stop-motion Pinocchio (2022). While Disney's interpretation always terrified and upset me, GDT’s flair for dark fairy tales makes this a dark fable about social oppression and disobedience filled with heart, hope, and a ton of love.

[I wanted to throw up a spoiler warning just case you don't want any small details ruined if you haven't seen the film! Maybe you do not mind — we all know the story and images and reviews are online — but not everybody has seen this version with this ending. Hopefully, you have seen the movie and want to read on, or maybe you haven't and want to read on anyway. Maybe reading this will make you want to watch the film? Whatever camp you fall into, I wanted to give you the option. Ok, let's carry on!

While I don’t have time to get into the wonderful voice work, or Sebastian J. Cricket, or how much I love Spazzatura the Monkey, I wanted to use this space to discuss GDT’s exploration of death, how he depicts beauty in darkness, and, most significantly, two particular characters: the Wood Sprite and Death.

In Pinocchio, Geppetto fashions the wooden puppet out of the grief of losing his son Carlo in an accidental air strike by Austrian forces. After passing-out drunk, the wooden boy marionette is brought to life by the blue Wood Sprite. Later on, Pinocchio encounters the Wood Sprite’s sister, Death.

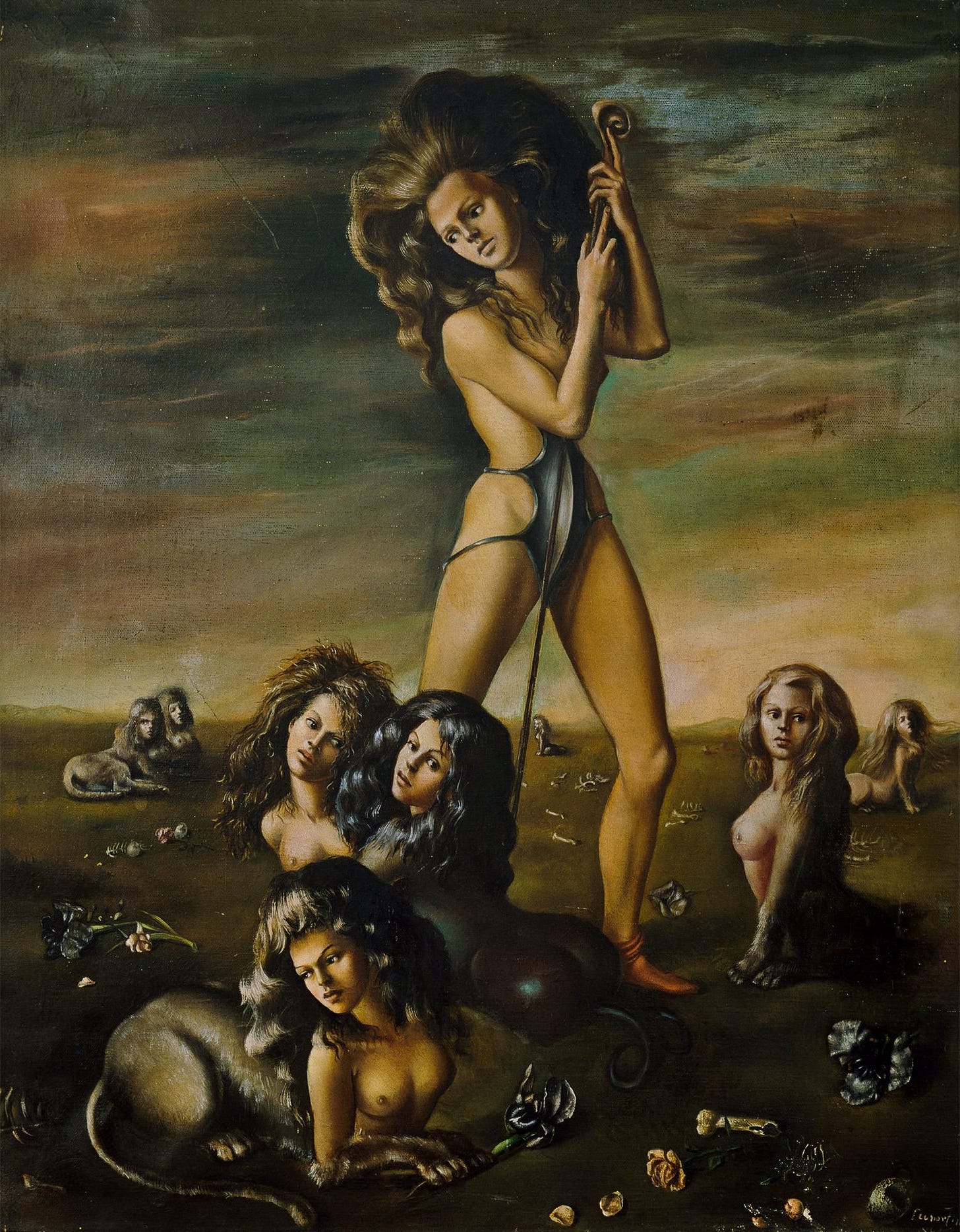

I love these characters for so many reasons. Death reminds me of a Leonor Fini artwork, notably one of her sphinxes, while the Wood Sprite (the Blue Fairy in Disney’s version) could be a Leonora Carrington or Remedios Varo deity, such as Varo’s Minotaur (1959). Known for her androgynous, alien figures with oval faces and almond-shaped eyes who more than resembled the artist herself, Varo’s appeasing yet magical protagonists always disarm any preconceived threat or strangeness because of who or what they resemble. In Minotaur, a cosmic blue (like the Blue Fairy) feminine horned creature is non-confrontational, welcoming her visitors or onlookers with a gentle, friendly greeting.

Varo’s Minotaur is both human and not human; thin-legged, delicate, and divine. The hood of a shimmering cloak surrounds her. Small white horns curve upward from each side of her head. Varo has painted a tiny galaxy instead of a crown of hair and holds a gold key in her elegant hands. I kept thinking of her when watching Pinocchio, but my mind kept going to another work by another artist: Toyen, and her forest messenger.

A lesser-discussed artist, Toyen (born Marie Čermínová but used the name Toyen since early adulthood) was a founder and the most celebrated/best-known member of the Czech Surrealist Group. After a period in Paris, Toyen returned to Prague in 1928 and helped establish the city as a significant centre for Surrealist activity. Toyen was good friends with members of the French Surrealist group, including Max Ernst, Yves Tanguy and Salvador Dalí, and the French writer, poet, and author of the Surrealist Manifesto André Breton and his third wife, the French writer and artist Elisa Breton.

Toyen was known for dressing in working men’s clothes and exploring gender stereotypes in their life and work. Some speculate they chose their name in a play on the French word ‘Citoyen’ (citizen), which gave a non-gendered identity, as well as being a play on the Czech words ‘To je on’, meaning ‘it is he’. The Czech poet, writer, and fellow co-founder of the Czech Surrealist Group Vítězslav Nezval once said that Toyen “refused... to use the feminine endings” when speaking in the first person.

Poselstvi Lesa [The Message of the Forest] is one of Toyen’s most enduring paintings. Painted in 1936, The National Galleries of Scotland website describes the artwork as follows:

The power of nature over the human world is a recurring theme in Toyen’s work which repeatedly centres on barren, dream-like landscapes, featuring lone girls, fragmentary female figures and birds. The interest in these themes originates in illustrations made for children’s books, but this soon took on a more bizarre and sinister appearance. Toyen was careful not to ‘explain’ the work, but instead left the viewer to explore the symbolic meaning. In common with many Surrealists Toyen had a keen interest in the writings of Sigmund Freud, with works seeming to respond to dreams and nightmares; suggesting a world of intense anxiety.

Also known as the Fairy with Blue Hair or ‘La Fata dai Capelli Turchini,’ The Blue Fairy or ‘La Fata Turchina,’ the Wood Sprite represents good and divine energy. She is Pinocchio's guide, his guardian angel constantly attempting to divert him away from risky deeds, yet the rambunctious little boy frequently ignores her well-intended advice. Pinocchio's rebellion is how he meets the Wood Sprite's sister, Death.

After Count Volpe convinces Pinocchio to join his circus and Geppetto arrives to take him home, the men have an altercation — a literal tug-o-war for Pinocchio — causing the wooden boy to be thrown in the road and hit by a car. Having arrived in the afterlife, Pinocchio is greeted by the card-playing Black Rabbits and sent forward to Death, the sister of the Wood Sprite. Death tells Pinocchio he is immortal, and while he will return to the mortal realm, cautions that his time in the afterlife will increase each time he returns.

Death is the character who interested me the most. While referred to in the production notes as a Chimera, I cannot help but see Death as a Leonor Fini Sphinx with a Venetian Carnival mask (we will come to the masks in a bit). Death is a Fini painting rendered in claymation for a Netflix audience. The feline guardian of the underworld is the perfect embodiment of everything cat-like for which Fini is so well known.

“I wanted to be like the sphinx”, said Fini, the self-styled ‘Sphinx of Surrealism’. An artist who depicted assured, proud, powerful, and non-subservient women — as well as a legendary cat worshipper — Fini revelled in her sphinx-like association. Leaving a legacy that reversed the preconceived gender associations surrounding the sphinxes, tropes of the Goddess, and the patriarchy of Surrealism, Fini's sphinxes, much like Death in Pinocchio, are often alone in their lairs or landscapes. Yet here, isolation and solitude aren't a form of weakness. Instead, they signify both empowerment and nurturing.

In her paper ‘La Feminité triomphante: Surrealism, Leonor Fini, and the Sphinx’, the author and scholar Alyce Mahon explores Fini’s association and self-imaging alongside the mythical creature. Mahon notes that ‘for the Surrealists, however, [mythology] offered a fantastic discourse with which to champion the irrational.’ She continues:

The myth of the sphinx was especially attractive, providing the perfect metatext for an exploration of forbidden desire, as well as encompassing the fantasy of the femme fatale, the potential of the city for the marvellous encounter, and a means of self-questioning by which logic and riddle can be set against each other. In the realms of male Surrealists, continues Mahon, “as Breton turned to the Sphinx as a means of reinforcing his knight-muse fantasy, Max Ernst and Salvador Dalí turned to the sphinx as the seductive intermediary between gods and humans, fantasy and the real, with an emphatic Freudian emphasis on the tale.

Breton incorporated the sphinx into his writings, most famously in Nadja, his seminal Surrealist novel, which included an encounter between himself and his eponymous doomed heroine in Paris’ Hotel Sphinx. Nadja is Breton’s sphinx: beautiful, forbidden and desired. Nadja is his flawed femme fatale, his fantasy and mystical apparition who he likens to a mythic creature. Yet when Nadja descents into madness, the illusion shatters, and the mystery and majesty vanish. She is no longer his exotic, marvellous creature. Madness in Surrealism is rife with double standards: men were celebrated, Romanised, heralded geniuses, and elevated. Women were destroyed, cast out, and victimised. Forgotten.

Fini challenged these stereotypes.

Fini’s subversive sphinxes bewitch and entice in their autonomous, non-acquiescent, seductive and, often (but not always), predatory nature. She painted the sphinx in various ways, usually as a form of self-portraiture: the sphinx, much like the cat, was her animal and a form of power. By charging herself with this entity, she was aligning herself with all its mythical symbolism. Fini believed this imposing creature was both nurturer and destroyer, a maternal creator of life in possession yet able to wreak havoc and destroy life as much as create. Fini put the feminine back into a traditionally masculine myth and imbued it with many more totemic associations.

Fini and her sphinxes, much like the various women Surrealists themselves, refuse to be categorised. Fini’s sphinxes are not necessarily violent, but they are women who no longer refuse to be quiet. They have the potential to invoke magic. Wild, unleashed, untamed, as the respected Surrealist scholar Whitney Chadwick noted: “Fini’s sphinx […] poses a question not about man, but about the woman artist’s place in the natural and metamorphic process that lies at the heart of the Surrealist vision of an art of fantasy, magic and transformation”.

Fini painted Petit sphinx garden (1943-44) while she was staying on the isle of Giglio, and she continued the theme after returning to Rome. Symbols of necromancy and death surround the sphinx, including a triangle, broken eggs, and an alchemical text. She continues these themes in Little Hermit Sphinx (1948), a volatile and suggestive painting that continues to be one of Fini’s best-known creations.

Chadwick has discussed Fini’s ability of fusion: masculine and feminine, human and bestial, wilderness and civilization, with work that was often darker, symbolically alluding to the forces underneath society and the murky goings-on that linger beneath any glossy surface. In Little Hermit Sphinx (1948), an open doorway reveals a ramshackle, unkempt building with peeling paintwork. An internal organ, which Fini confirmed was a human lung, dangles from the threshold, while leaves, a broken eggshell, and a bird’s skull are strewn on the floor. The sphinx’s black cloak reveals a cat-like paw.

Fini’s biographer Peter Webb said the painting was about Fini’s hysterectomy in late 1947. As Webb writes in his gorgeous biography of the artist, ‘Little Hermit Sphinx is a self-portrait that reflects Leonor’s state of mind after the trauma of her operation.’ The lung, meanwhile, was painted ‘because of the beautiful pink colour.’ It’s a painting of anxiety, trauma, and finding beauty in the darkness.

Although I can see Fini’s sphinxes in Death, I also see another facet of Fini’s life and work. Death’s face in Pinocchio is almost like a Venetian carnival mask — we can say its similar to the masks worn in the ritual scene of Stanley Kubrick's final opus, Eyes Wide Shut (1999). There is a Fini connection to this, too.

Fini had a flair for the carnivalesque nature of dressing up and the ritual of masquerade. She once recounted,

While still a child, I discovered the importance of masks and costumes. At fourteen, I walked through the streets of Trieste with a girl of my age, with foxtails stolen from our mothers sewn to our skirts. To dress up is to have the feeling of changing dimensions, species, space. You can feel like a giant, plunge into the overgrowth, become an animal, until you feel invulnerable and timeless, taking part in forgotten rituals.

Masks appealed to both the childhood introvert and adult extrovert sides of Fini's character, and she was famed for her love of masked balls. In a series of photographs by André Ostier, Fini wears several cat-like masks, and in 1949 she made a variety of masks for balls, attending them in the style of birds, cats or cat-birds. Two years later, in Paris, a book was published titled Masques de Leonor Fini (Masks of Leonor Fini), its pages etched with Sphinxes, skeletons, costumed figures, and masked faces.

Masks allowed Fini to indulge in her love for all things carnivalesque, transformative, and magical while confronting her mortality. As she once said, ‘I have always loved – and lived – my own theatre. To dress up, to cross-dress is an act of creativity…The real excitement for me was the joy at preparing my costume. I used to arrive late, about, midnight, lightheaded with joy at being a royal owl, a large grey lion, the queen of the underworld…’

Towards the end of GDT’s Pinocchio, the boy dies in an explosion. In the afterlife, he asks Death for his life back to save a drowning Geppetto. Pinocchio knows this will make him mortal, but it’s a sacrifice he’s willing to make. After passing in the selfless act, Pinocchio is brought back to life by the Wood Sprite. Following his return to the living, we see Pinocchio at various stages over the years, enjoying a full, rich life and outliving Gepetto and his loved ones (including Spazzutura, whose last scene made me weep more than at any other point in the film), before embarking on his travels for new adventures.

“The one thing that makes life precious, you see, is how brief it is,” says Death at one point in the film. It’s a beautiful, potent quote, rich with poignancy. Fini once said, ‘I wear masks in order to be someone else, and my masks, on my living, moving face, are Immobility. I like that...Death on my face...or perhaps an ideal life. A life without movement. Movement is a sequence of innumerable deaths.’

Chadwick said Fini’s sphinx was ‘both sorceress and the image of death.’ Light and dark, life and death. Two sides of the same coin, much like the Wood Sprite and Death. Both serve as reminders that while there is tumult and turmoil in life, there are small pockets of joy, love, hope, and glimpses of great beauty in the darkness.

Thank you for reading Love Letters During a Nightmare. If you enjoyed this, please share, tell your friends, and/or sign up for a paid subscription to enjoy additional articles, lecture transcripts, and PowerPoint presentations/PDFs. If not, you are welcome to Tip Me/Buy me a coffee. Merry Christmas, Happy Holidays, and see you in the New Year!

Love Leonor Fini, haven't seen the film yet but will watch! Thanks for writing this.

Love how this is all strung together with wonderful pieces of art