Spellbound

Women Artists, Surrealism, and Hollywood

Surrealism and Hollywood, Surrealism in Hollywood, and Surrealism’s affect on Hollywood’s are themes that I have been dipping into for the best part of a decade. I have spent the last year writing something along these lines to be met with lukewarm enthusiasm by those who can push this thing forward. Maybe it’s a dead end, I don’t know, but this part of art history is wildly fascinating to me, and I was hoping it would be to some of you, too. Until that day comes, here are some observations and musings and automatic thoughts I have long pondered, stake my claim on, and stand behind.

In 1937, Salvador Dalí penned a wildly enthusiastic essay titled ‘Surrealism in Hollywood.’ In one key snippet, Dalí wrote:

I am just back from Hollywood, and there I have heard the word Surrealism in every mouth. They have even officially announced surrealistic passages in forthcoming films. This only goes to prove that Hollywood has suddenly discovered all that it has always dimly desired in the subconscious.

Many of you will be familiar with some, if not all, of Dalí's Hollywood adventures: his failed attempts to make a film with the Marx Brothers, his successful dream sequence for Alfred Hitchcock's Spellbound (1945), and his mid-1940s collaboration with Disney, Destino, not seen until the early 2000s. Stories centring on Dalí’s attempts to crack Hollywood with his giant scissors and Hitchcockian visions continue to endure. Still, it is an unfair assessment to say Dalí was the only Surrealist who made an impression on Hollywood and for who Hollywood left its mark. Man Ray lived in Hollywood for eleven years — from 1940 to 1951 — painting and taking portraits of various movie stars. On moving there he said, ‘there was more Surrealism rampant in Hollywood than all the Surrealists could invent in a lifetime.’ Surrealism's effect on Hollywood extends beyond the Catalan artist. Why does Surrealism in Hollywood neglect women and predominately revolve around Dalí?

Women Surrealists had a much quieter yet enduring influence on Hollywood, and they did it without the Dalían fanfare. I argue, constantly, that Elsa Schiaparelli (I wrote about in an earlier edition of this newsletter) staked her claim to Hollywood first, and much more stylishly.

During the 1930s, Schiaparelli’s Paris Atelier was a bustling hive of Hollywood stars shopping for their personal wardrobes. Schiap was one of the first — perhaps the first — to put her client Joan Crawford in shoulder pads. Soon the fashion designer Adrian Gilbert (known more generally as Adrian, coincidentally Schiap’s friend), and Hollywood followed, as Schiaparelli’s flourishes began influencing the stars’ on-screen costumes.

In one key snippet from Elsa Schiaparelli: A Biography by Meryle Secrest (Penguin: 2015), Schiaparelli’s assistant Bettina Bergery is quoted as saying, ‘Marlene Dietrich tried on hats, crossing her celebrated legs and smoking a cigarette exactly as she does in a film, but no one has ever done in real life before.’ But this was real life. In another, animated paragraph, Bergery vividly describes the scenes when Hollywood flocked to Place Vendôme to great visual effect:

The prettiest and neatest of all the Hollywood stars…is little Norma Shearer. All the girls in the shop love Claudette Colbert — Merle Oberon and her waves of perfume that make them faint — Katharine Hepburn choosing the things that all American girls always buy in the boutique — Lauren Bacall with her aristocratic Polish face and her hoarse gutter voice. How Garbo was the best-dressed person at your last year’s cocktail party—how small she looked and how she never stopped talking…and how Ginger Rogers, after a day on an airplane [sic] from New York, danced all night…

Widely popular with Hollywood actresses off-screen, Surrealist fashion captured a broader audience in 1939 with the release of George Cukor's The Women. Featuring costumes by Adrian, Schiap’s Surrealist presence was all over the film, prominently hinted at in Rosalind Russell's triple-eyed sweater. Pardon me for quoting myself, but when I wrote about the film for AnOther Magazine in 2019 I said:

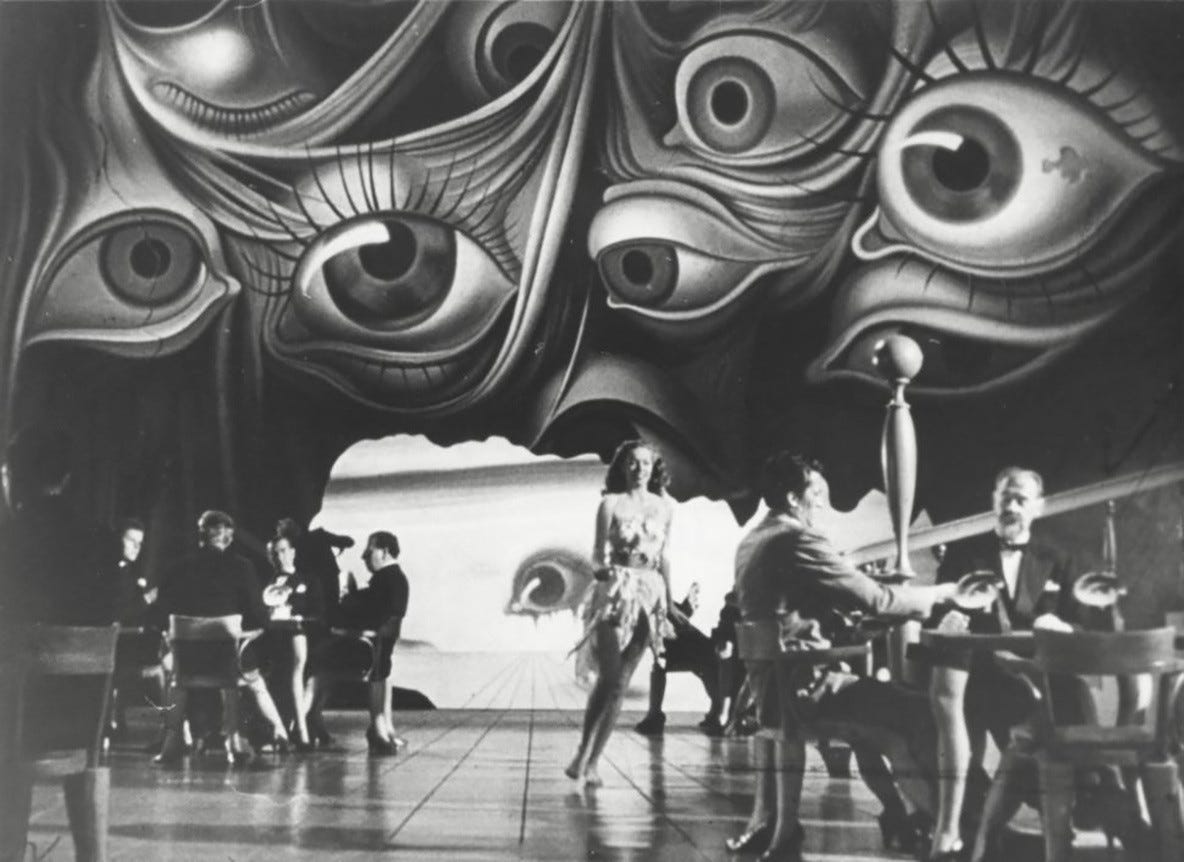

The eye is one of the most prominent Surrealist motifs, and in this moment, Adrian manages to reference not only Schiaparelli’s eye brooch (made in collaboration with Cocteau), but work by her collaborator Salvador Dalí, including an eye brooch Dalí designed, and the eye-cutting sequence in 1929’s Un Chien Andalou (directed by Luis Buñuel and Dalí). In 1945, Dalí would create an eye-laden dream sequence for Hitchcock’s Spellbound.

The Women’s infamous Technicolor fashion sequence, ironically despised by Cukor, is akin to a Surrealist dream sequence, and Schiaparelli’s work is clearly referenced. It was a perfect example of her potency as Surreal Couturier, and how her work could infiltrate Hollywood to greater effect.

In 1952, Schiaparelli designed Zsa Zsa Gábor gowns for John Huston’s Moulin Rouge. Starring Gábor as chanteuse Jane Avril and José Ferrer as the artist Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, the film went on to win various Academy Awards, including Best Picture and Best Director for Huston, and Best Actor for Ferrer. Most significantly, and we may say stingingly, the Best Costume Design award went to the movie's lead costumier Marcel Vertes; Schiaparelli's name was absent from the ceremony. The snub set a precedent: the failure to reward the work, impact, and longevity of women Surrealists.

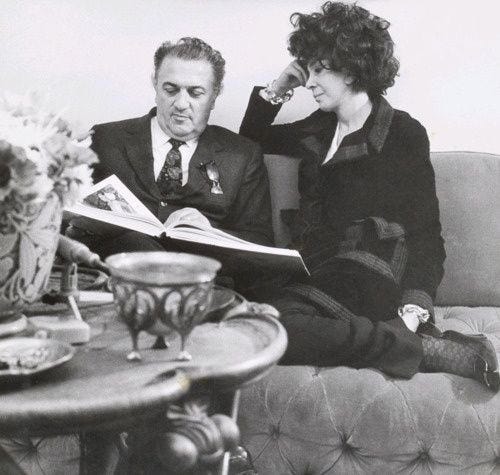

Some women Surrealists have only recently received acknowledgement for their Hollywood contributions but still have a long way to go before the film industry take note of their work. The Italian-Argentine artist Fini, renowned for her self-assured work, powerful women, and passion for cats, worked as a costume designer on Federico Fellini's 8½ (1963). Her name remains absent from the film's credits, and while she now appears on the film's IMDb, there is still a while to restore her reputation as a critical cinematic contributor.

Someone else wildly discussed in academic circles, but not so much in film history, is Leonora Carrington. Carrington's mythic works are a rumoured influence on the Mexican filmmaker Guillermo del Toro, especially in such works as Pan's Labyrinth (2006). As Lora Markova and Roger Shannon have noted in their article ‘Leonora Carrington on and off Screen: Intertextual and Intermedial Connections between the Artist’s Creative Practice and the Medium of Film':

According to [Francisco Peredo] Castro, the parallels between Pan's Labyrinth and Carrington's work involve the labyrinth itself, the stone arch/doorway, the tree as a portal between fantasy and reality, as well as the character of the faun (a mythological creature) and the magical rituals performed by the protagonists.

In 1945/46, the film producer David L. Loew and director Albert Lewin, seeking a painting for their film The Private Affairs of Bel Ami (1947), founded the Bel Ami Art Competition (Bel Ami International Art Competition). Based on the 1885 novel Bel-Ami by Guy de Maupassant (1850-1893), they sought a painting about Saint Anthony's temptation that would play as important a role as Ivan Bright's portrait of Dorian Grey had in Loew's Oscar Wilde adaptation the previous year. Lenora Carrington and Dorothea Tanning were the only two women out of eleven artists competing for the accolade (Leonor Fini had declined the invitation), with the winner to be decided by Dada artist Marcel Duchamp and the art historian Alfred Barry. Although the trophy, as well as the $2,500 prize fee, went to Max Ernst, both Carrington and Tanning would both design for theatre productions. Two women with cinematic visions.

Surrealism is still making its mark on Hollywood, and women artists are vital to why specific images and certain flourishes continue to endure and bewitch. There are other stories to tell — about women Surrealists and Hollywood, about women Surrealists in Hollywood, and about how one impacted the other, and vice-versa. Now travel has opened up to the States again, I’ll be digging to some archives in the Spring and hope to flesh out some things. Maybe one day there will be a complete tale, in book form, to tell.

Thank you for reading and subscribing!

I am thinking of changing the name of this newsletter to something more snappy and less long-winded. Thoughts are welcome.