On my laptop sit many works-in-progress, ideas I have toyed with since the start of the pandemic (exactly) two years ago. Or even longer. I spent time tweaking things initially written a decade or so ago, and pitched three very different book proposals — one of which I am still attempting to rework and hone to a more successful model. Others, I will return to another time. So, I thought I would share a work-in-progress that falls into the latter category, something I first initiated at the inaugural Death Maidens Conference back in 2017, a glimpse into a larger idea about women Surrealists and death and a project I will, eventually, return to in a more complete form.

In André Breton's seminal Surrealist novel, Nadja, he narrates an encounter with a mysterious woman on the streets of Paris. He describes this young woman as mentally unstable or mad, a judgement so many men of the movement repeatedly place upon women (and a dismissal that has nonetheless seen these overshadowed women rediscovered in recent years). I do not read Nadja as a madwoman but as a mysterious entity. Nadja is never fully present; what Breton interprets as her flightiness is instead an ability to traverse words; she is a being neither grounded in reality nor entwined in death. She is unsteady, not entirely whole, elusive and difficult to pin down. As she says, ‘I am the soul in limbo.’

The late French painter and philosopher René Passeron has discussed how the war impacted the early days of Surrealism and, in particular, male artists. The imprint of death on their psyche. Benjamin Péret, Max Ernst, Paul Eluard all enlisted and served overseas; however, André Masson experienced the most severe trauma and post-traumatic stress. ‘Mobilized in 1915, he was seriously wounded in April 1917 in the Chemin des Dames battle.’ Passeron wrote, ‘dragged from hospital to hospital, including the Maison Blanche Psychiatric Hospital, he would only be discharged in 1918.’ In Mémoire du Monde (World Memoirs), his 1974 memoir, Masson explained that his sense of self 'had been forever damaged,' which gave a visceral sense of the macabre to his paintings. Later, during World War II, Lee Miller would become one of the only female photojournalists to document the frontline.

While war dominated the nightmare visions of men, women explored death in different ways, including through bodies, bones, desires, and blood. When we think of death and women’s bodies knowing extreme pain, we often refer to Kahlo, who endured pain and pain and suffering throughout her life. Disabled since childhood, miscarriages in adulthood, and death filled her art and detailed her diaries. Death has become entwined in Kahlo's legacy, her inclusion of Mexican death masks and traditions never too far away.

Kahlo's fractured body served as a daily reminder of her mortality. At sixteen, a bus accident resulted in health problems and disability for the rest of her life. She painted lying in bed, paralysed and in a body brace, and immobile for multiple years. After polio crippled Kahlo's legs, she walked with leg braces, and in 1953, after gangrene had set in, her right leg and foot had to be amputated below the knee. In 2018, London's Victoria & Albert Museum staged Frida Kahlo: Making Herself Up, an exhibition focusing on her art and wardrobe. The hugely popular show presented Kahlo's pain alongside her artistic talent; her vibrantly painted prosthesis was one of the items on display.

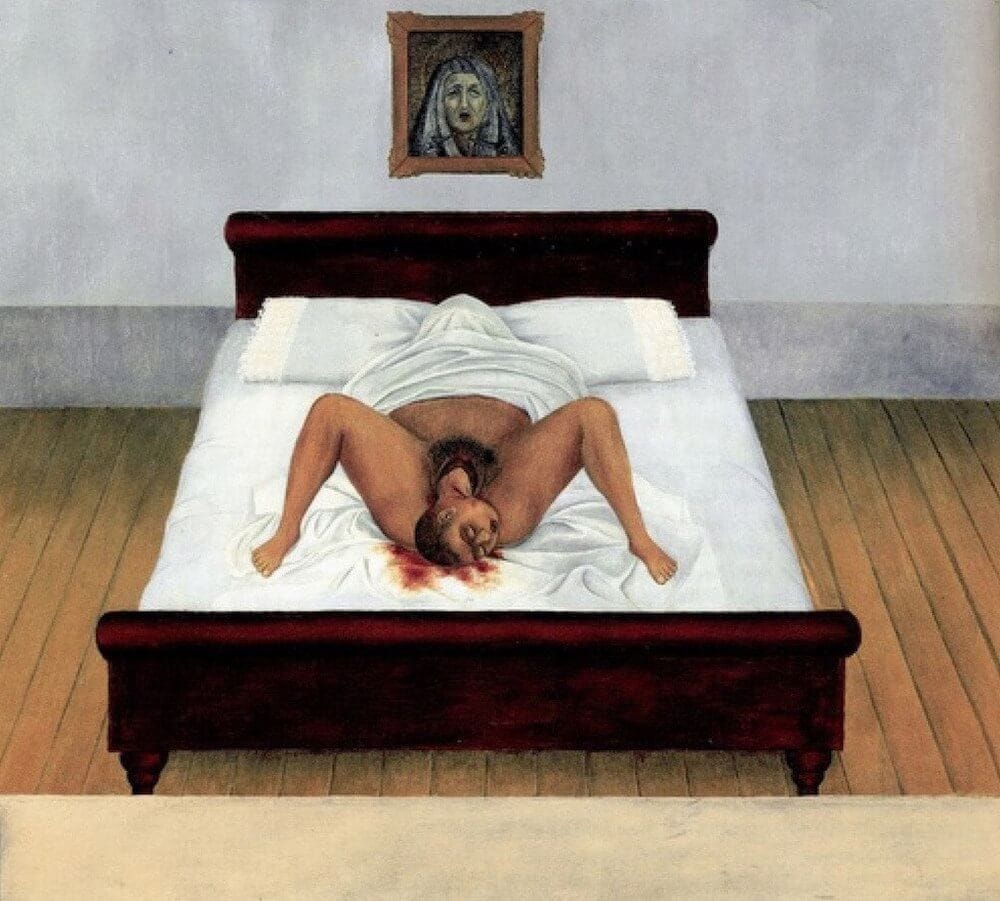

Kahlo’s paintings frequently evoke the life cycle and the intrinsic relationship between life and death, the body as an atlas of trauma. In her book Women Artists and the Surrealist Movement, the scholar Whitney Chadwick notes that Kahlo's ‘terrifying self-portraits in which childbirth rather than the Surrealist act of love forms the connecting link in an external cycle of love and death.’ Kahlo ‘used paintings as a means of exploring her own body and her consciousness of that reality.’ Maternity became an internal conflict for women like Kahlo as they appeared more violent than nurturing in their rendering of the subject. Her 1932 painting My Birth has been credited as one of the few depictions of childbirth within Western art that stresses the ‘cyclical relationship between fertile eroticism and death by placing the self at the centre of the cycle.’ The violence of the painting has a greater significance to death than the birth of a new life.

While Kahlo is, justifiably, a name on the tip of people’s tongues, there are other artists I tend to think of first in their depictions of Surrealism and death. I have spent swathes of time thinking about Leonor Fini's relics and her objets trouvés; her found collection of bones collected on the beach in Nonza, near her Corsa home. Likewise for the darkness that flows through Tanning's doors and childlike visions (you can read about that here!).

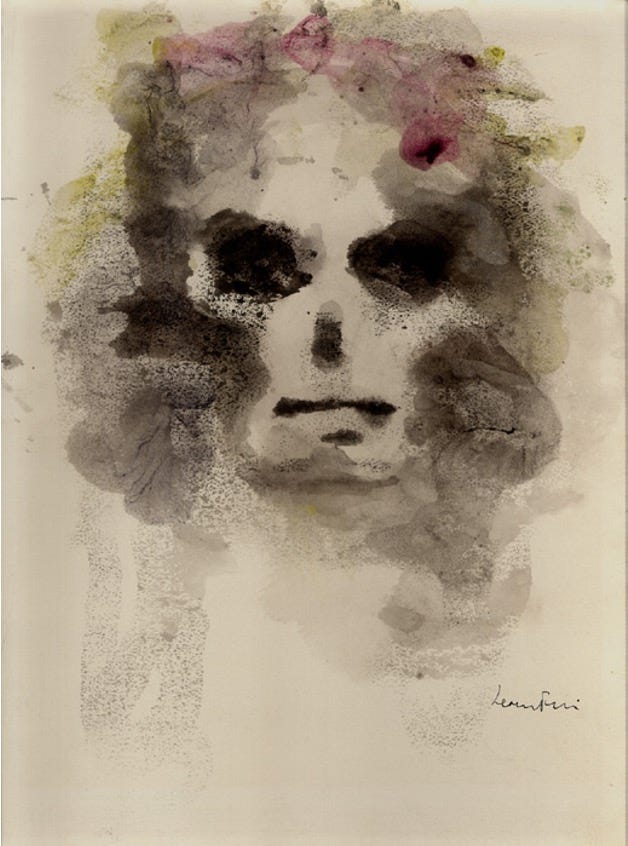

I wear masks in order to be someone else, and my masks, on my living, moving face, are Immobility. I like that...Death on my face...or perhaps an ideal life. A life without movement. Movement is a sequence of innumerable deaths.

- Leonor Fini

In a series of photographs by André Ostier, Fini is seen wearing several cat-like masks, and in 1949 she made a variety of masks for balls, attending them in the style of birds, cats or cat-birds. Two years later a book was published in Paris titled Masques de Leonor Fini (Masks of Leonor Fini), the book’s pages etched with Sphinxes, skeletons, costumed figures, and masked faces. As I wrote in my chapter on Fini for the edited volume Making Magic Happen, ‘some of Fini’s work explored darker themes, symbolically alluding to the forces underneath civilization and the murky goings-on lingering beneath any glossy surface. Referencing Small Guardian Sphinx (one of many sphinxes Fini painted), Chadwick noted how it “recalls the figure of the sphinx as sorceress and image of death. Here representations of necromancy and death surround the hybrid creature: a triangle, broken eggs, and a hermetic text”.’

In thoughts of death and Surrealism, I also think about Remedios Varo’s focus on death focuses on the fruit’s magical associations, a beautiful example of the magical realism that flowed throughout Varo’s paintings. Naturaleza muerta resucitando (1963) features a table where various spinning fruit circle above, implying supernatural activity and an unseen presence. Varo has painted the centre of the cosmos, a joyful celebration that is not so much deathly or feared but harmonious and celebratory. It feels keenly appropriate after the two years the world has experienced (and continues to grapple with as things evolve and change). It feels like a rebirth.

Darkness is not necessarily ominous, but it has felt highly plentiful during the past couple of years (and remains even now). But Spring is here, and with the change of the season comes the light. It feels different this year — something more hopeful, finally. A rebirth, and hopefully, things will improve for all. We do our best to find the light in the world's destruction. Art and death. Beauty, life and hope. Now more than ever, we must seek some light in the darkness.

Thanks for reading!

If you are interested, you can now read Love Letters During A Nightmare in the new Substack app for iPhone (which is better than clogging up your inbox IMO).