On Tuesday 29 November, I'll be on a panel at Warwick Art’s Centre discussing female vampires following a screening of Ana Lily Amirpour’s brilliant vampire-western A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night (2014). I know most of you are not West Midlands based, or even UK based, but please join if you are! In light of this event, today’s newsletter follows a similar vampiric theme.

In 1962, Valentine Penrose wrote her seminal historical novel/biography on Erzsébet Báthory. Titled Erzsébet Báthory la Comtesse sanglante, and translated into English in 2002, the book is more widely known as The Bloody Countess.

Sometimes referred to as the female Vlad the Impaler or compared to Gilles de Rais (who was known for murdering hundreds of young boys), Countess Elizabeth Báthory de Ecsed was a sixteenth-century Hungarian noblewoman and serial killer who believed the key to everlasting youth and beauty was to bath in the blood of attractive young women. Báthory was married, and her husband was silently aware of her inclinations; she had children, but in terms of her sexuality, was generally only attracted to — or turned-on by — women. Surrounding herself with a coterie of ladies (made up of lady’s maids and witches) to help her capture, torture, and kill, Báthory soon realised the blood of the young peasant girls she was capturing was not the key to her eternal youth, so began procuring young, titled, females. She needed ‘good blood,’ quite literally.

Báthory’s bloodlust and proclivities were practically out of a De Sade book – she even surpassed De Sade in depravity. As Georges Bataille (who I love and will probably write about at some point) wrote in the Tears of Eros, ‘De Sade did not know of Erszébet Báthory’s existence, but doubtless her atrocities would have roused his most vicious excitement.’

The Bloody Countess ticks all the boxes of a typical gothic novel, but with more blood and heaps of atmosphere. As an extract reads:

Vampirism, occultism, alchemy, necromancy, tarot cards, and, above all, ancient black magic, were the fruits of this city of narrow streets that was surrounded by forests. It was here that peddlers came to replenish their stocks of little books with the irregularly printed characters, their pages ornamented with woodcuts portraying devils holding their tails under their arms and looking askance at those who had conjured them up…The immense cursed silence invaded everything.

Given her own personal interest in divination and her sexuality (speculation surrounds her ‘very close friendship’ with fellow Surrealist artist and poet Alice Rahon), some people assumed Valentine Penrose had incorporated facets of herself (the magical elements and queerness, not the murdering, obviously) into the book.

Valentine Penrose (née Boué) was a French-born Surrealist poetess, author, and collagist who possessed a deep and unwavering interest in the occult. She ‘liked to think of herself as a witch,’ and references to mysticism, alchemy and the occult pervade her poetry’. She was known to have communed with nature, used verses as incantations, and wrote effectively on female desire. Valentine considered magic an antidote to Surrealist bourgeois ideology, and mystical influences organically infused her work. An extract from her ex-husband Roland's biography, Roland Penrose: The Friendly Surrealist, reads:

She had an arcane connection to the primordial elements of female creativity: she understood the secrets of the stars, the ways of animals and the intimate lives of plants. Astrological charts were her street maps, and her Tarot cards gave her insights into the future.

Valentine was a hands-on practitioner and intrepid student of mysticism. She read tarot cards and cast horoscopes at Farley Farm House while Lee Miller (her friend and Roland's second wife) was pregnant with her son Antony Penrose (Incidentally, a forthcoming film is in the works about about Lee Miller focusing on her photojournalism during World War 2. Kate Winslet has been cast as Lee and Roland Penrose, a man with his own sexual proclivities, is due to be played by Nordic Vampire Viking hottie Alexander Skarsgård). When Antony was older, Valentine would unnerve him with her accuracy. One of her tarot decks is still at Farley's; another is in the National Gallery of Scotland in Edinburgh.

She took her tutelage seriously. During her life, Valentine studied under the esoteric master Count Galarza de Santa Clara in Egypt, as well as taking courses in Oriental philosophy at the Sorbonne and Hindu philosophy at the University of Paris. She even encouraged Roland to embrace Tantra during their marriage. Through her body of work, Valentine assisted to forge and strengthen ties between Surrealism and the occult, as well as queer art theory, sexuality, and British Surrealism.

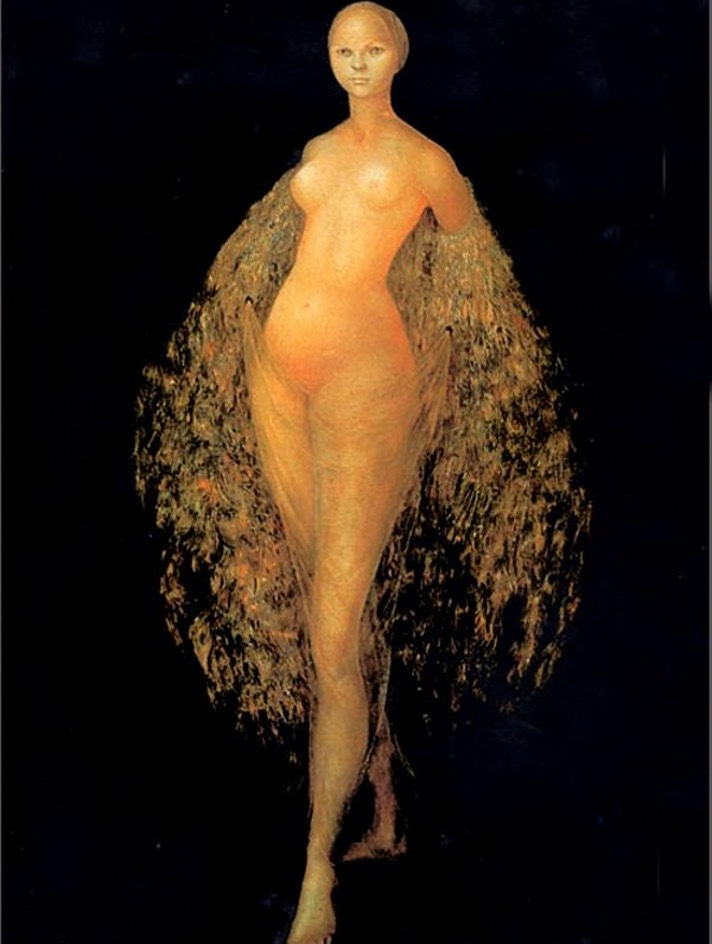

Valentine’s mythic and visual poetry may remind us of Leonora Carrington and Angela Carter’s stories, particularly their subversion of traditional fairy-tale gender norms. As Alicia Ostriker notes, ‘it is thanks to myth we believe that woman must be either “angel” or“monster”.’ Very often, the women of these stories are Witches or Sibyls governed by forces attuned to the occult and Witchcraft; these women are powerful entities, and a far cry from the femme-enfant mould crafted by the male Surrealists’ imaginations. Leonor Fini’s witches are also another excellent example.

The subject also allowed women to confront specific ‘taboo’ issues, such as non-heterosexual relationships and the monstrous feminine (Valentine had a close friendship/love affair with the artist Alyce Rahon who was married to Wolfgang Paalen). Valentine perceived the gothic’s potential as an outlet for women experiencing and transmitting their passions, especially those of a strange and the illicit nature. With her knack for voicing the dark side of womanhood, Valentine always had a fondness for local mysteries and bizarre occurrences and enjoyed seeking these out. She also had an infinity to the moon.

There is a degree of lunar repetition in Valentine’s poetry and The Bloody Countess. Her poem Herbe à la lune (1935) was noted for being ‘performed under the sign of the moon,’ while her ‘treatment of the esoteric is always feminized’. The moon is an icon of femininity in both Surrealism and magic. It is la lune in French and appears a frequent motif in many Surrealist works by male and female artists (from Magritte to Varo, Carrington, and Fini). The Surrealist film Un Chien Andalou (1929) contains that famous moment when Buñuel, slicing a woman’s eye, appears to undergo a supernatural transformation while looking at the moon. It was also reworked and re-presented by Meret Oppenheim from a more material, visual, female perspective via her iconic gloves.

Oppenheim’s hairy gloves evoke werewolf associations, yet the red lacquered nails feminise the gloves without relinquishing any of the creature'’s physical strength or character. The redness may also prompt associations to the ‘blood-red’ acts of violence or murder while suggesting a symbolic reference to the female menstrual cycle. In many ways, Valentine presented Báthory as a Surrealist collage: a weaving of the high and the low, the monstrous with the feminine, evil with beauty. To quote scholar Elsa Adamowicz, ‘the Surrealist combination of beauty and monstrosity cannot contain the monster, and the resulting being achieves freedom and independence.'

Valentine Penrose, ‘the benign white witch of Farley Farm’, died on 2 August 1978 at the now-famed East Sussex Surrealist farmhouse where Roland had nursed Lee to the end the previous year. The Esoteric Surrealist — or Surreal Occultress — who created magic through collage and wove spells into poetry, Valentine retaliated against traditional Surrealism while provoking, expanding and engaging with many of the movement’s themes in her own unique way. She was a phenomenal talent, incredibly underrepresented, and curious about everything. For those who recognised her for who she was, there is no doubt how much they adored her. I think the final quote by Tony Penrose provides a fitting conclusion:

Her passion for plants and natural things and how deeply angry she would be if someone cut down a tree or shot an animal. She was detached but never aloof. Never cold to anyone. Very cuttingly witty about people she did not like. Immensely kind and patient with young people who all loved her. Everyone adored Valentine – the people in the village, on the farm, our visitors, my school friends - maybe because she was not of our world but always interested in us.

Thank you for reading Love Letters During a Nightmare. If you enjoyed this, please share, tell your friends, and/or sign up to a paid subscription where you can enjoy additional articles, lecture transcripts, and PowerPoint presentations/PDFs.