The Melancholy of Magritte

The Belgian Surrealist artist Rene Magritte (1898 - 1967) was a master of trickery. His work encourages the viewer to look longer and harder, absorb the work, and not form immediate conclusions. Most effectively, Magritte’s art was a darkly wry look into the everyday, subverting preconceived notions on corporate life and the monotony of capitalism. As a result, his work can appear both innocent and menacing in equal measure.

Known for his juxtaposed, intelligent, often sly, witty paintings that played with artistic representations, one of Magritte’s best-known works is The Treachery of Images (1928-1929), an image of a pipe proudly proclaiming ‘Ceci n’est pas une pipe.’ The work is a sharply wry, humorous proclamation that is, in fact, true. We are not looking at a pipe, but we are looking at a painting of a pipe. There were times when Magritte took things further by utilising the idea that images were artistic representations rather than representations of truths or reality by pairing seemingly opposite objects together. Or to place them within environments alien to their natural habitat. This wildly effective and ever so subtle technique made Magritte’s art influential in everything from cinema to advertising.

In cinema, the similarities between Magritte’s paintings and David Lynch’s films – especially Blue Velvet – are striking. Both excel at creating disquieting atmospheres that penetrate the surface of supposedly ‘ordinary’ situations. In Lynch’s case, a suburban neighbourhood’s ordinariness – all white picket fences, perfect roses, and cloudless blue skies — is disturbed by a severed ear on the edge of a perfectly manicured lawn. Nothing is as it appears, look closer, and you will spot the distortion. In this respect, both Magritte and Lynch are very similar; beautiful work riddled with darker undertones.

Magritte’s 1928 painting The Lovers II depicts a couple kissing, their faces concealed and swathed in fabric. The subject and tone draw comparisons to a tragic event in the artist’s life. When he was fourteen years old, Magritte’s witnessed his mother’s lifeless body retrieved from the river, her soaked nightgown wrapped around her face. Such an image would have had an immeasurable impact on the young man, whose work bristles with melancholy. Yet Magritte once disputed — or maybe encouraged? — such a claim by saying, ‘my painting is visible images which conceal nothing. They evoke mystery and, indeed, when one sees one of my pictures, one asks oneself this simple question, “What does it mean?” It does not mean anything because mystery means nothing either, it is unknowable.’

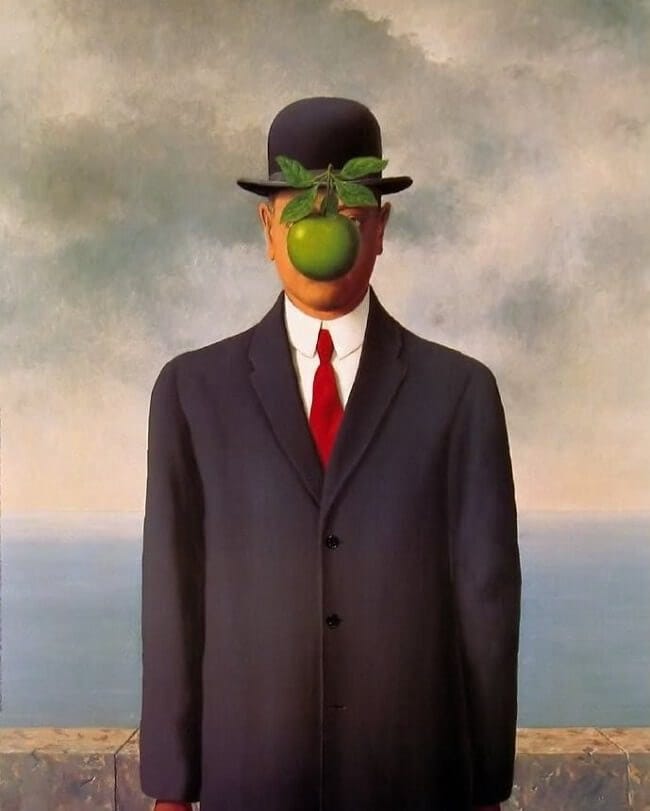

Art became a catharsis, a way to unburden suppressed feelings and emotions. Magritte’s grey-suited men were a nod to the emotionally repressed of his generation required to conform to sociological and bourgeoisie conventions of employment, and its uniform of the suit, tie and bowler hat. We now refer to this as the Mad Men era and even Magritte, due to his part in advertising, became part of this establishment.

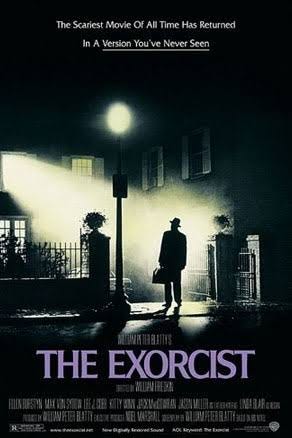

One of Magritte’s lesser spoken but greatest movie legacies is that his painting Empire of Light (L’empire des Lumières) (1953-54) influenced the poster for The Exorcist (Dir: Friedkin, 1973). The image is true to Magritte’s trademark juxtaposition of daylight and evening that plays with all sense of spatial awareness. However, it draws you into a false sense of comfort. It’s a psychologically unsettling painting, filled with menace and foreboding: the street lamp glowing at the centre of the painting, the blue skies penetrated by the tall tree shrouded in night, the illuminated room glowing behind the tree and obscured by branches, perfect fluffy clouds in the sky and the dark grass below.

In the poster for The Exorcist, we see the same eerie darkness juxtaposed with the beam of light emerging from the bedroom, and the single glowing streetlamp indicate how Magritte’s influence has crept into the poster. However, rather than the blue skies with their fluffy clouds, this image is entirely shrouded in darkness; a bleaker, altogether more supernatural illusion hints at a sense of foreboding lurking in the house. In addition, the single silhouetted figure of Father Lankester Merrin (Frank von Sydow) appears is also very Magritte-like: a faceless, suited male figure wearing a bowler hat. It’s a figure that is perhaps the artist’s legacy. In a 1965 radio interview, Magritte commented on his 1946 painting, The Son of Man:

At least it hides the face partly well, so you have the apparent face, the apple, hiding the visible but hidden, the face of the person. It's something that happens constantly. Everything we see hides another thing, we always want to see what is hidden by what we see. There is an interest in that which is hidden and which the visible does not show us. This interest can take the form of a quite intense feeling, a sort of conflict, one might say, between the visible that is hidden and the visible that is present.

The beauty of Magritte’s work is his universal appeal to all audiences. It can be equally effective in promoting an intensely frightening film as it can one aimed at children. The 1992 film Toys (Dir: Levinson, 1992) was primarily influenced by Magritte’s The Son of Man and instantly noticeable in both the sartorial choices of Robin Williams’ character and the set design. Replacing the black business suit and bowler hat with the red adds the sense of fun dynamic inhabited by Williams’ character. It makes him a more endearing character, appealing to the (inner) child rather than the faceless and rather fearsome character whose face we do not see. Even the poster’s tagline ‘Laughter is a state of mind’ is a play on the notorious Surrealist figure André Breton’s remark that Surrealism is based on ‘psychic automatism in its pure state, by which one proposes to express - verbally, by means of the written word, or in any other manner - the actual functioning of thought.’ The childlike exuberance of Williams’ characters is very in-tune with the Surrealistic ethos and the freedom of the mind that the group endorsed.

One of the most recognised uses of Magritte’s artwork occurred in the 1999 remake of The Thomas Crown Affair (Dir: McTiernan, 1999). While Norman Jewison’s original 1968 film, starring Steve McQueen and Faye Dunaway, centred on a bank robbery, John McTiernan’s remake took place in an art gallery. The targeted painting may have been a Monet, but many Magritte references were visual and verbal. Pierce Brosnan’s Thomas Crown is as enigmatic as Magritte’s faceless gentleman. He wears a bowler hat, keeps his cards close to his chest and is as mysterious as Magritte’s gentlemen — he is even referred to by Rene Russo as ‘the faceless businessman’. Magritte himself could have painted Brosnan’s Crown. Instead, here is his faceless businessman, his son of man, as plain as day for all to see, emerging from the canvas. I recently wrote about the Surrealism at the root of The Thomas Crown Affair for Real Crime, should you fancy a more in-depth reading (if you have already read the piece, thank you).

Magritte’s of both screen and canvas will linger whenever we see a suited businessman in a bowler hat holding an umbrella. Yet Magritte is not a ghost; his influential presence is an example of Surrealism’s true, endearing, enduring legacy: nothing is mundane. Everything is extraordinary.

Love Letters During A Nightmare is a series of newsletters by me, Sabina Stent, about things I adore, enjoy, and generally have on my mind. It’s currently free (for now), but if you enjoyed reading and would like to subscribe, please do! Also, if you enjoyed and would care to buy me a coffee/contribute to my research fund, you can do so via my Ko-Fi Page. Thank you for reading!