Last week, during my most recent trip to Los Angeles, I walked past the John Sowden House. Designed by Frank Lloyd Wright in 1926, the imposing property is often referred to as the ‘Franklin House’ or ‘Jaws House’ because it appears as either a shark or Mayan Temple, depending on the viewer’s perception. I always make a point of walking from Franklin Village to Los Feliz (or vice versa) whenever I am in town, purely to see the house. From a distance, I attempt to peer past the railings and glimpse at the ghosts who continue to reside there. I’ve never been inside — it’s used for events and functions and films these days, including scenes of Curtis Hansen's L.A. Confidential (1997), Martin Scorsese's The Aviator (2004) and episodes of Ghost Hunters, but friends who have attended ‘dos’ assure me it’s extraordinary. It’s a house filled with secrets, ghosts, and dark mythology, and I would still love to live inside. Sometimes I am asked whether the house's connection to one of the most notoriously brutal murders in history would deter me from this desire. My profile photo is me outside the house, which pretty much answers the question.

Los Angeles is a city of ghosts and hauntings — its history is as dark as it is glittery, starry, and gold. It is these ghosts of the past that call to me and keep me coming back.

A few months ago, David Fincher revealed that Mindhunter, one of the best television shows of the latest ten years — one of the best television shows of all time — was no more, for reasons including the series cost too much money for such a small audience. I do not believe the ‘it was not lucrative enough’ line (both seasons were critically praised and universally popular) and that the audience figures didn’t justify the expense. Can an audience really be niche if most subscribers are watching? I have watched both seasons multiple times and devoured John E. Douglas and Mark Olshaker’s book Mindhunter: Inside the FBI's Elite Serial Crime Unit, on which the series is based. The show was insightful, intelligent, elegant, and non-exploitative, which true crime can be prone to do. We will never know what became of Holden Ford, Bill Tench, and Wendy Carr and if they managed to discover the crimes of and apprehend Dennis Rader, aka the BTK killer, or BTK Strangler. Part of me refuses to believe it really is the end; after all, there was a two-year gap between 2017’s first season and 2019’s second, plus Rader was inactive for ten years. Maybe the trio will return in 2029. We can only hope.

I'm telling you this because one of my favourite Instagram accounts recently shared a photo of a naked mannequin wearing a fur stole, provoking a follower to comment, “did this fall out of Dennis Rader’s pocket?” Rader, a serial killer who had dolls on his property, acquired his nickname BTK, or ‘Bind, Torture, Kill,’ due to his sadistic sexual fantasies, but the correlation between serial killers, mannequins, and sex dolls has been well documented. Jeffrey Dahmer stole a mannequin from a Milwaukee department store. Herb Baumeister, nicknamed Herbert the Pervert’ and ‘The I-70 Strangler,’ the notorious Indiana serial killer — suspected of killing over 20 men — kept mannequins in his swimming pool. Mannequins have a significant role in art history, too.

In 1938, on entering the International Exhibition of Surrealism, visitors were ushered down the ‘Street of Mannequins,’ immediately finding themselves among sixteen attired mannequins, each dressed in a different Surrealist artist’s vision. One of the most notorious installations was Dalí’s Rainy Taxi, which, when peered into, led viewers ‘to discover a scantily clad female mannequin, crawling with snails, perched on the back seat in a cascade of water.’ A male chauffeur wearing a shark’s head was in the front seat, while the girl, in the back, appeared to be rotting.

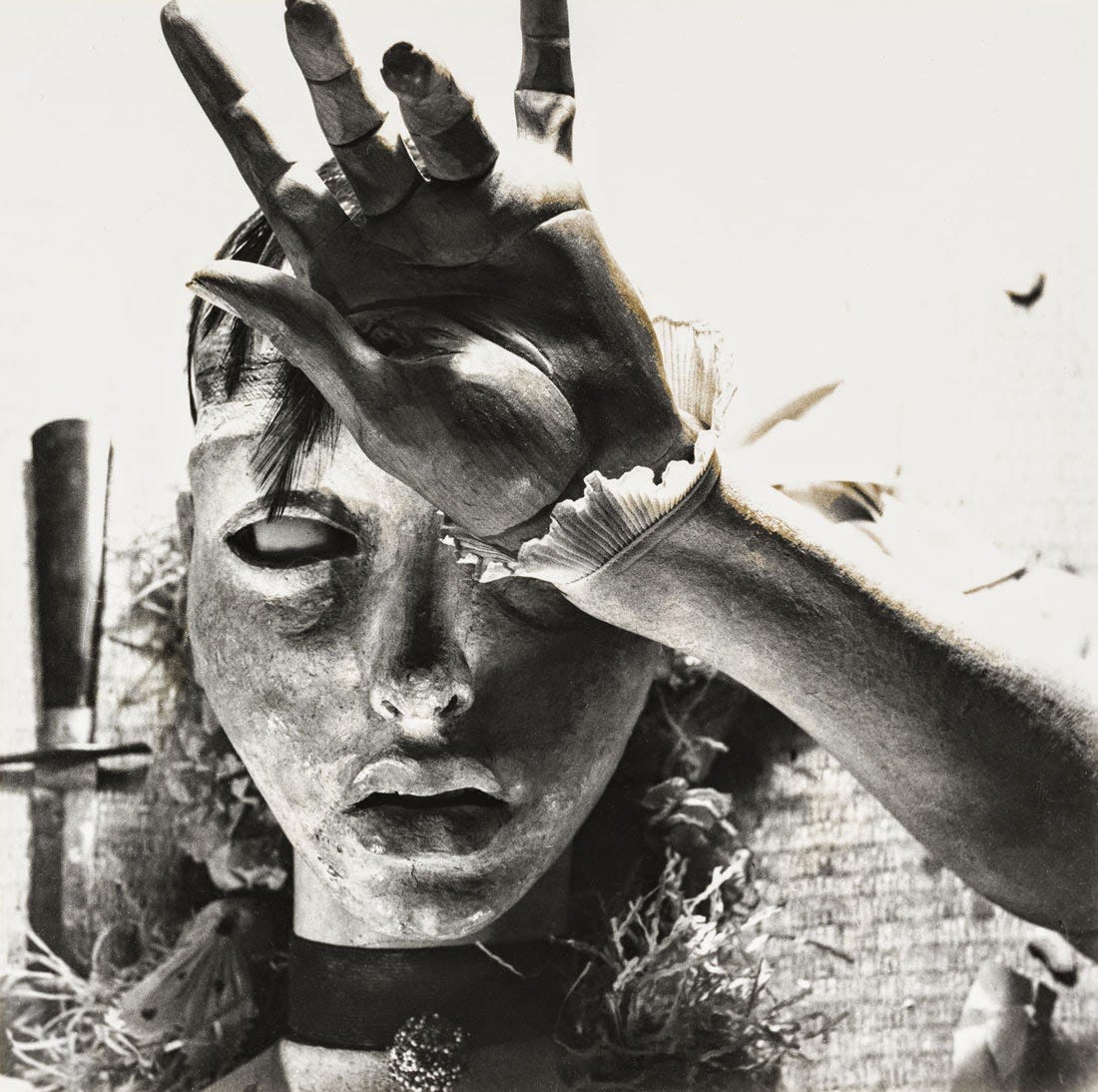

Hans Bellmer’s famously sexualised dismembered dolls and mannequins remain infamous. David Hopkins writes that ‘the Surrealists, in the wake of certain paintings by Georgio de Chirico, had turned the mannequin into something of a cult’. Ruth Hemus, an authority on Women Dadaists, too, has commented that ‘dolls, puppets and mannequins became chief components of the Surrealist movement, demonstrated most radically and graphically in the photographic works of Hans Bellmer, where the doll stands for the eroticised, sexualised, and often violated female body.

*Disclaimer: unsure of how sensitive some readers are, I have included more censored images in this piece as examples, but do feel free to source the others — or ask me — should you wish to see the more graphic versions*

I keep thinking about the body, specifically the violated female body, and how much the corpse of a disembodied woman reminds me of some artworks by men who equate the disruption of a woman’s body as an almost creative process. As the art historian and author Whitney Chadwick writes, ‘the female body – assaulted, fragmented, rewritten as subject and verb, interior and exterior – became the Surrealist symbol par excellence.’

A knife is a phallic signifier, but both are instruments of harm, essentially interchangeable in situations of sexual violence. In 1943, Maya Deren made her landmark short film Meshes of the Afternoon. One of the film’s reoccurring symbols was a knife. In 1947, a knife severed and dismembered the torso of twenty-two-year-old Elizabeth Short, posthumously known as the Black Dahlia. On 29 July of that year, Short's mutilated lifeless body, bisected at the waist, was discovered on a vacant patch of land in the Los Angeles Leimert Park area. The young woman's body had been drained of blood, resulting in a pallor so white the woman who found her assumed she was a mannequin in two parts. Short's breasts and mouth were both slashed, and multiple lacerations were also on her body in the act of extreme brutality. Fascination lingers, and conspiracy theories continue to abound, some radical, some more plausible, of who was responsible for the Black Dahlia murder.

Leimert Park is now a residential neighbourhood, and the vacant lot is now a grass verge outside somebody’s home. There is no marker on the perfectly tended lawn. It appears nondescript to those unaware of the location’s history but occasionally attracts those with a morbid fascination to pay their curious respects. I’ve been one of those people, visiting with an equally like-minded friend as we made a pilgrimage in April 2022 to what is now a perfectly tended neighbourhood. The grass is green and manicured. You wonder how many passersby connect to such a horrifically dark event.

The 2019 television mini-series I Am The Night acknowledges how art and violence are frequently — and sometimes unavoidably — linked. Based on ‘One Day She Darkened,’ Fauna Hodel’s autobiography/crime book written with J. R. Briamonte, Fauna was the Granddaughter of Los Angeles physician George Hodel, owner of the Sowden House from 1945-50, and the most famous prime suspect (whether you choose to believe it or not) in the Black Dahlia murders. The series had a modest following, but because of low ratings has not left too much of a dent in Black Dahlia lore that books and podcasts by members of Hodel’s family (such as the Root of Evil podcast) have. Yet rather than the actual lore, what struck me when I watched the series years ago was the emphasis on Hodel as an avid art collector.

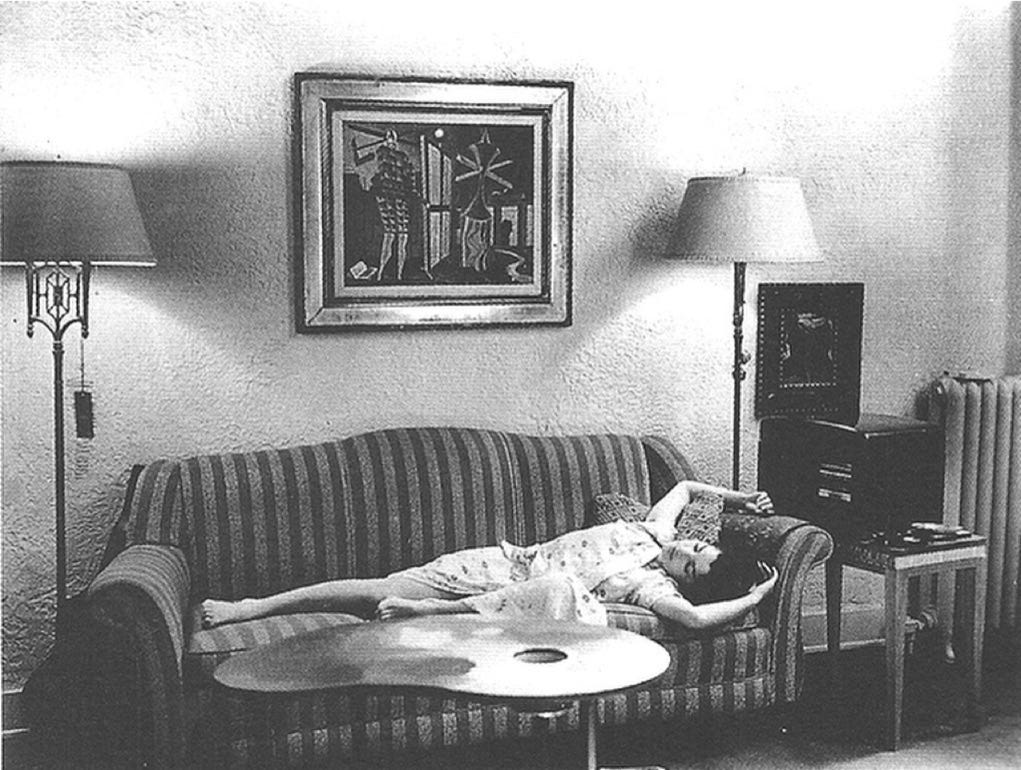

Man Ray lived in Los Angeles for eleven years, from 1940 to 1951 (that’s a whole other folder of my research, and I’ve written a little about it here). Man Ray and Hodel knew one another during this time, and various sources note their friendship, but little substantial evidence remains of how close they really were (did ‘friends’ mean cordial acquaintances or did they socialise regularly?) Yet in thinking about this piece, my mind went to a photo of Juliet Browner (who married Man Ray in a 1946 Hollywood double wedding with fellow Surrealist artists Max Ernst and Dorothea Tanning). It’s an image I have shared before, a 1945 photo where Browner sleeps on the sofa, posing in the style of the minotaur, a popular mythological creature amongst the Surrealists. Browner’s arms are bent to her side, and one of her legs is bent. Rather than being dominated by the minotaur, she has transformed into one herself, occupying a once-masculine space. Short’s dismembered body, unceremoniously dumped on that patch of grass, was poised in a similar way. Steve Hodel, son of George, has perpetuated the under substantiated theory (if anyone wants to commission me to write a book pursuing this claim, please get in touch), of how his father’s friendship with Man Ray and his notably works Minotaur (1934), and Observatory Time: The Lovers (1936) led the physician to murder Short and in her death, create his ‘own sick Surrealist masterpiece.’

While I Am The Night could not use famous artworks for licensing reasons, Hodel’s real art collection consisted of works by many Surrealists artists, including Rene Magritte, Salvador Dalí, and Georgio De Chirico. In Susanna Moore’s brilliant book In The Cut, Detective Malloy (played by Mark Ruffalo in Jane Campion’s excellent 2003 film adaptation) described the bodies of the murdered women as ‘splayed, abused, dismembered, disarticulated.’ The description always reminds me of Short. In I Am The Night, Flora gazes at each painting and sculpture, horrified to see how they have depicted women in compromising, fragile, and vulnerable depictions.

I think about all this as I look at the house. I have just purchased another book about Short’s murder for my collection from Counterpoint Records in Franklin Village. As always, I stop outside the house and take a selfie. Last year, looking through Man Ray’s archive at The Getty, I noticed there was no mention of Hodel in his correspondence. I walk on.

I often wonder why I find the darker portions of history, art, media, and someone’s psyche so compelling; why I am fascinated by someone's psychology, of what makes them think and act out their actions. I think of Elizabeth Short and how this girl who died an undignified, horrific death became the eternal Black Dahlia of Los Angeles lore. I think of art by the women and men of Surrealism, my various art textbooks and bios and the serial killer and true crime books scattered on my shelf. I think of that patch of grass on Leimert Park, of the history and basement of the Sowden House, where the murder and blood draining were alleged to have taken place. I think of all the lost girls we still don’t know about, who haunt the glittery stars, hotels, and bars on the Boulevard. I think about Man Ray’s decade in Los Angeles, of how much more I’m yet to uncover. And I think of the haunted city, the darkness behind the glitter, and how the ghosts of the past continue to call me and keep me coming back.

Sabina, I've read this multiple times and keep coming back to it. Wonderful piece!

Do you think Duchamp’s ‘Étant donnés’ owes anything to Short? It’s always made me think of her and I’m not entirely sure why.