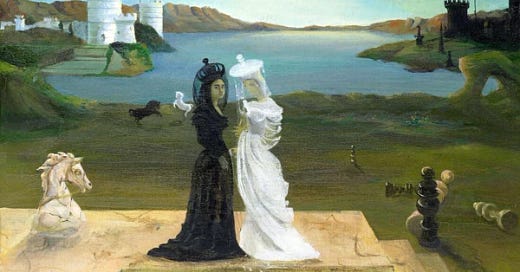

In 1944, Muriel Streeter (or Muriel Levy, her married name) painted a double portrait in which she featured alongside her close friend and fellow artist, Dorothea Tanning. In the painting, titled The Chess Queens, both women stand shoulder-to-shoulder, wearing the monochrome colours of black and white, two Queens on a Chessboard in a Surrealist dream landscape. The Tower is in the background, while the Knight, a white horse, is still standing. Both Pawns have fallen, while real horses, animals rather than pieces from the game, frolic happily in the background. But these pieces are not opponents. They stand together as formidable allies.

I find Streeter so fascinating for various reasons, one of the reasons being we do not hear her name as frequently in discussions of women Surrealist artists. She recently appeared in Routledge’s gorgeous Surrealism, Occultism and Politics: In Search of the Marvellous (edited by Daniel Zamani, Victoria Ferentinou, Tessel M. Bauduin), and was one of the artists included in LACMA’s perfect (and one I will always regret missing) exhibition ‘In Wonderland: The Surrealist Adventures of Women Artists in Mexico and the United States’ (29 January – 6 May 2012). While I know, and hope, that her rediscovery is imminent, the sparseness of her name in textbooks and articles only heightens my intrigue. I become a moth to the flame.

Born in Vineland, New Jersey, in 1913 (d. 1995), Tanning once referred to Streeter as “the most beautiful girl in New York.” By the 1940s, Streeter had established a reputation as a notable Surrealist painter, with her first solo exhibition at the Julian Levy Gallery in 1944 (the year she would marry the arts patron and gallerist, having met Levy a few years prior). Her work appeared in Peggy Guggenheim’s 'Art of this Century: The Women' exhibition of 1945, the 1949 Whitney Annual, and another solo show at the Levy Gallery in 1950. After moving to Arizona in 1969, her work became more abstract and grander in scale, with paintings of the Tucson landscape and local Cacti. She passed away in 1995, and her final exhibition took place at Anna Howard Gallery in Washington Depot, Connecticut.

Streeter painted The Chess Queens in retaliation to Max Ernst's sculpture, The King Playing with the Queen, also of 1944. In her painting, there is no king in sight, only defiant women standing side-by-side, united in this game of chess in a Surrealist landscape to topple Surrealism's patriarchal nature and male power games. The painting also serves to highlight the allegiances forged between women Surrealist artists. In her fantastic book The Militant Muse, Whitney Chadwick highlights the friendships and correspondence between women artists between the wars (including Leonora Carrington and Leonor Fini, and Lee Miller and Valentine Penrose). Female solidarity within the artistic community.

Women Surrealists often painted or photographed each other. Fini painted Carrington, Dora Lee Miller photographed Dora Maar, Maar photographed Fini, etc.), and Tanning immortalised Streeter in Portrait of Muriel Levy. (I often wonder if being sometimes cited as Streeter and other times using her married name of Levy has obstructed access to her? Even here, I am unsure how to cite her correctly, but as she signed her art as Streeter, that’s what I have gone with). In the portrait, Streeter’s likeness fills the canvas, her face beaming down from the sky, while the tiny figure of Tanning stands in the bottom right-hand corner of the frame. A powerful entity complete with her trademark red lipstick.

The friends had a close rapport and friendship. In one gorgeous garden-themed correspondence dated 1947 and tinged with Surrealist humour, Tanning writes:

“Too, this is the moment for sowing seeds — Phobia, Amnesia, and the everblooming bulbous Syphillis, noted for its long-stemmed, fiery pistules, delightful for cutting as well as a prodigal — if dubious — garden attraction. I don’t know if you have the dwarf-bedding Vagina — it does well if backed up by a staggered row of Nymphomania: also looks surprisingly well if mixed in casually with oval or glossy Testiculum.”

The intimacy of sharing domesticity.

Like many researchers, a subject is never thoroughly interrogated, never placed back on the shelf and locked away. I have themes and ideas and things I’ve been playing around with for over a decade. The beauty of working on an artist, or an art movement you have worked on for a long time, is that no writing, even a piece that has languished for years, is never wasted. I have drafts on my computer from things ten years ago that I’ve spun and weaved into recent work, and I am constantly returning to specific artists. I used to find I could recall particular periods by who I was working then. Nothing ever ends or changes. Time is circular, and so much is about discovery or rediscovery. Ideas are constantly tweaked, and sometimes you meet a fork in the road and choose to take the other route. Even now, I consider this piece a work-in-progress.

The first issue of this newsletter was about chess — specifically Dorothea Tanning’s love of chess and the fantastic Netflix series 'The Queen’s Gambit.' Chess was a reoccurring motif in Surrealism, particularly for Tanning, who described the game as “something voluptuous, close to the bone.” For Streeter, chess became a statement of friendship, akin to writing letters or painting portraits. The Chess Queens has become synonymous with unity. Like Tanning’s portrait, it is another entry in the canon of women painting/photographing their friends, who happen to be fellow women artists.

My favourite photograph of Streeter was taken by Lee Miller in 1946, with the artist lying on the grass, basking in the Los Angeles sun. Her gaze is to the camera, and she seems so self-aware, her gaze so intent. Streeter's hand is to her brow, not so much in a moment of contemplation but of leaning across and noticing a dear friend with a camera ready to capture your likeness. It reminds me of the photos of other women Surrealists taken by their friends because there is an ease to it, a candid familiarity that appears organic, whether it was intentional or not. There’s also something about Streeter’s direct-to-camera stare, informing us that she is much more than a subject. She knows it, and her friends know it, too.

Streeter gives a similar stare in a self-portrait of the same year. Standing paintbrush in hand, paint rag in the other, she looks side-eyed at someone just out of sight, as though she has been disturbed while working. It’s rapidly become one of my favourite self-portraits because her expression appears to be cutting detractors down to size with a single glare. Streeter reminds us that she is a talented artist who just so happens to be the most beautiful girl in New York. These titles are not mutually exclusive. And she won’t let us forget it.

Love Letters During A Nightmare is written by me, Sabina Stent, about things I adore, enjoy, and generally have on my mind. It’s currently free to read, but if you enjoyed, please subscribe and share. Also, if you enjoyed and would like to buy me a coffee/tip me, you are welcome to do so. Thank you for reading!

I met Muriel Streeter thanks to Dorothea Tanning, and she and I became close friends (my corresponence with her, of which I have both sides, numbers some 300 letters). I also knew Julien Levy beginning in 1972, when I was sixteen years old (I met Muriel in 1982, after he had died). In any case, this is an excllent article. I am trying to decide what to do with Muriel's archives and letters and would liek to donate them to an institution. I tracted down many of her paintings for her, for example the one that Joseoh Cornell bought, as she had lost track of them over the years.