“What art is, in reality, is this missing link, not the links which exist. It's not what you see that is art; art is the gap.”

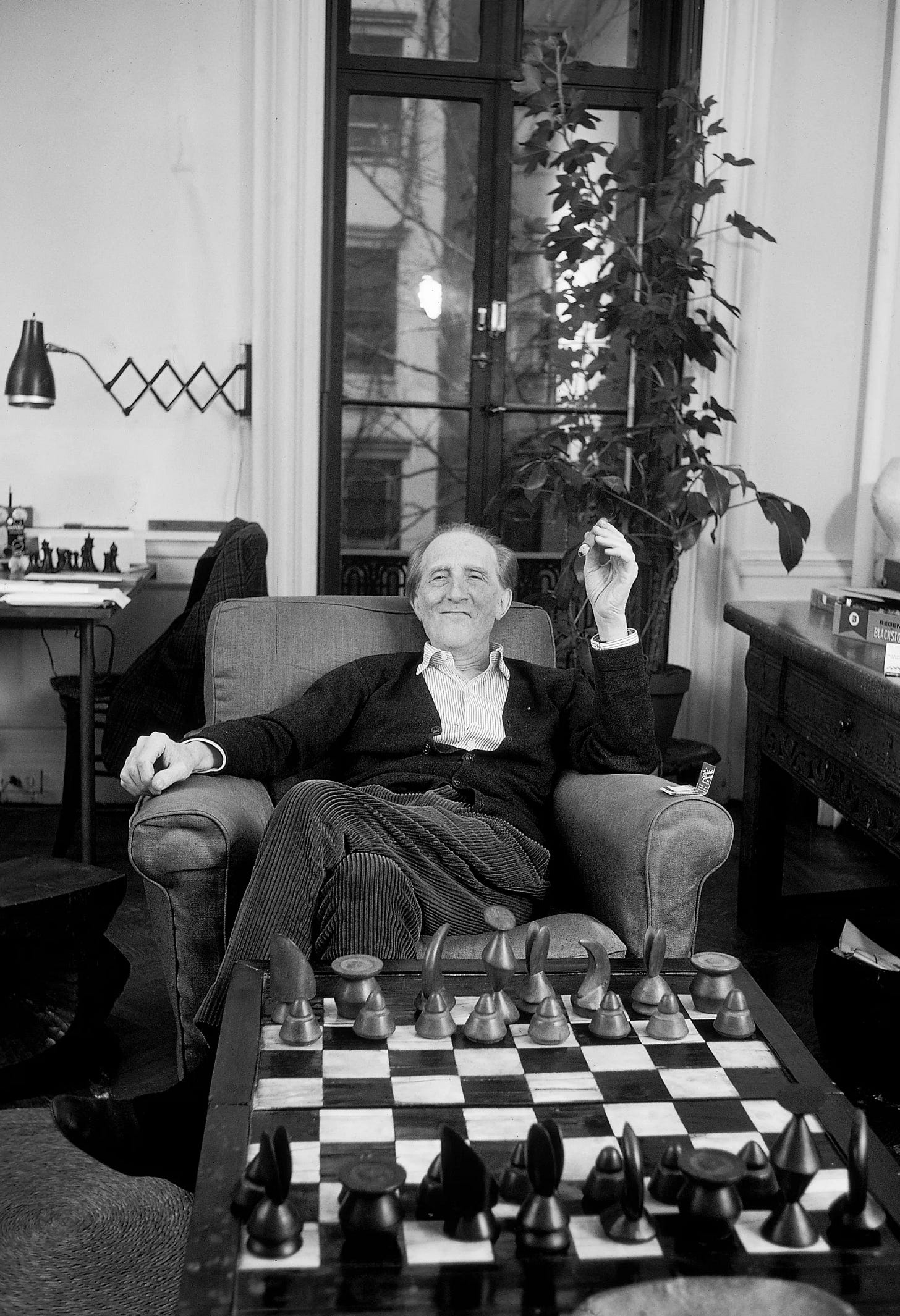

To say Marcel Duchamp’s Étant donnés surprised the art world would be an understatement. After a prolific art career and association with the Surrealists, Duchamp had traded his lengthy art career for competitive chess, which he had (by this time) been playing for almost twenty-five years. However unbeknownst to everybody, Duchamp had spent 1946 to 1966 working privately and secretly on Étant donnés, his last major artwork, in his Greenwich Village Studio.

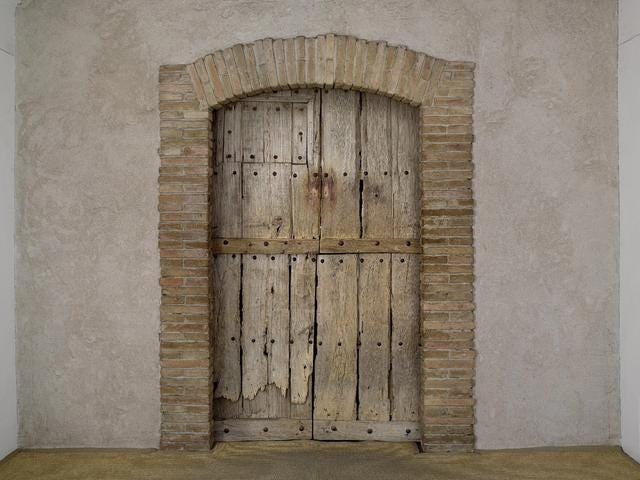

Étant donnés (1946 - 1966) is a provocatively voyeuristic assemblage, visible via two peepholes on the wooden box concealing the work. The artwork depicts a naked woman lying on her back, her legs apart and her face hidden. She is laying on a grassy, mossy embankment, holding a gas lamp in one raised hand. You could say she appears splayed and abandoned. You may be able to see where I am going here….

A dear friend mentioned Étant donnés after I published my previous newsletter because of its highly evocative of Elizabeth Short imagery. The similarity is uncanny — from the splayed body to the nakedness and even the greenery, practically grass verge-like, although the artwork has more colour, a more thriving nature than the abandoned patch of grass where Short's bisected corpse was dumped. I considered mentioning Étant donnés in my previous newsletter, but I wanted to give the work its own space — partially because of the work’s timeline and because of the multi-layered (on and off canvas) nature of the piece, which I wanted to write a little bit about here. This is in not way conclusive, and I will continue to write more about this theme in fits and bursts. But, for now, Étant donnés.

Étant donnés is composed of various materials (an old wooden door, nails, bricks, brass, hair, twigs, glass, and even an electric motor concealed in a cookie tin), but the main focus is the naked, spread female figure. The body in the assemblage was based on two people: Maria Martins, a Brazilian sculptor and Duchamp’s partner from 1946 to 1951 modelled for the body, while the arm clutching the lamp was that of Alexina "Teeny" Duchamp (née Sattler).

Let me briefly tell you about Teeny.

Teeny moved to Paris in 1921 with her sights set on becoming an artist and, in 1929, married Pierre Matisse, son of Henri Matisse, the father of her three children. In 1951, via Dorothea Tanning, she reconnected with Duchamp (who she had first met in 1923 at a Parisian ball given in her honour), and the couple married in New York in 1964. Teeny, who had acquired many artworks in her 1949 divorce from Matisse, worked for a spell as an agent and broker for artists including Brâncuși and Joan Miró.

I should do a deep dive on her one day.

Back to Duchamp. Duchamp stipulated that Étant donnés be installed and viewed after his death, and it was transferred to the Philadelphia Museum of Art in the 1960s under the watchful eye of Anne d'Harnoncourt, a young curator who went on to become the museum’s director. So detailed was Étant donnés that Duchamp prepared a 4-ring binder, his ‘Manual of Instructions’ detailing how to assemble and disassemble the piece, and in 1969, a year after Duchamp’s death, Teeny and her son Paul Matisse, Duchamp’s stepson, installed the work and made it available to the public. It is still on view at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Due to my interests, I often draw lines between things, and ponder how one feeds into the other. Some of these may be factually accurate, some just my way of seeing the world. In the last instalment of my newsletter, I wrote about Salvador Dalí’s voyeuristic Rainy Taxi of the 1938 International Exhibition of Surrealism, Hans Bellmer's fetishistic mannequins, the fragmented female body present in so much Surrealist art, and George Hodel, the physician, art collector, and most famous suspect in Elizabeth Short's murder. Was Hodel a fan of Duchamp, too? Hazarding a guess, and given his artistic interests, I would say he was. That being said, I cannot see his name in any of the indexes of my Black Dahlia / Elizabeth Short / Hodel books I own.

I’m so curious whether Duchamp was aware of Hodel, and the extent of his knowledge of Short’s murder. Short’s life was taken in 1947, a year after Duchamp started work on the piece, which leads to ponder whether Étant donnés was somehow inspired by and a reference to The Black Dahlia murder?

Duchamp became an American citizen in 1955, four years after Man Ray left Los Angeles, and the two men were friends. Duchamp, in fact, passed away at his home in Neuilly-sur-Seine after eating dinner with Man Ray and the art historian Robert Lebel. Around 1am, after his guests had left for the evening, Duchamp collapsed in his studio and died of heart failure. I already spoke about the Man Ray / Hodel connection in the previous newsletter, so I don't want to repeat myself. But looking at Duchamp's assemblage and Short's bisected corpse, the similarities are striking — including how the arm and leg are positioned.

The author and art historian Mary Ann Caws once said, ‘Surrealism brought about a new way of looking. Like much else in that movement and manner of thinking, the world has two senses: what it looks like and how it looks at the world outside it and then inward, to an “interior model”. In my March 2022 newsletter about Dorothea Tanning, I wrote about doors as a motif in her work, as both an entry and exit point of the dark, unsettled psyches that begin during girlhood. I quoted Katherine Conley, who said, ‘Tanning’s paintings redefine domestic space for young women as claustrophobic, haunted by malevolent spirits: “we are waging a desperate a desperate battle with unknown forces”’. One of the paintings I mentioned was Tanning’s 1942’s Children’s Games, a provocative piece of girlhood alluding to Alice in Wonderland. As the girls pull the paper off walls, as their hair and bodies get sucked into the fissures, more flesh and orifices are exposed underneath. We can see the lower body of a third girl lying on the floor while a door is seen in the background.

I keep thinking of the juxtaposition between Tanning's feminist-Surrealist doors, opening and closing entry and exit points into girlhood, sexual awakenings, and darker sides of the female psyche, and the wooden, door-like box of Étant donnés revealing the Elizabeth Short-like figure within.

I’m fascinated by this Venn diagram of Surrealist art and Elizabeth Short, and while I found no correspondence or mention of Hodel in Man Ray’s personal artefacts at the Getty Archive in 2022, I am still so curious. Did Duchamp know about Hodel? Did he ever talk about Short or Hodel with Man Ray? Did they talk about how people made connections between their art and the young woman who died with no dignity? Did they think Hodel was an art hack or a serious collector, an eccentric doctor or a psycho, and what did they really think of the Sowden House?

And, most intriguingly, did Hodel own any art by women Surrealists?

As usual, sitting writing this left with more more questions than answers, I think of a specific quote by Duchamp: “what art is, in reality, is this missing link, not the links which exist. It's not what you see that is art; art is the gap.”